Pathophysiology, Aetiology, Risk Factors and Implications For Manual and Manipulative Therapy In Practice

Carotid Artery Anatomy:

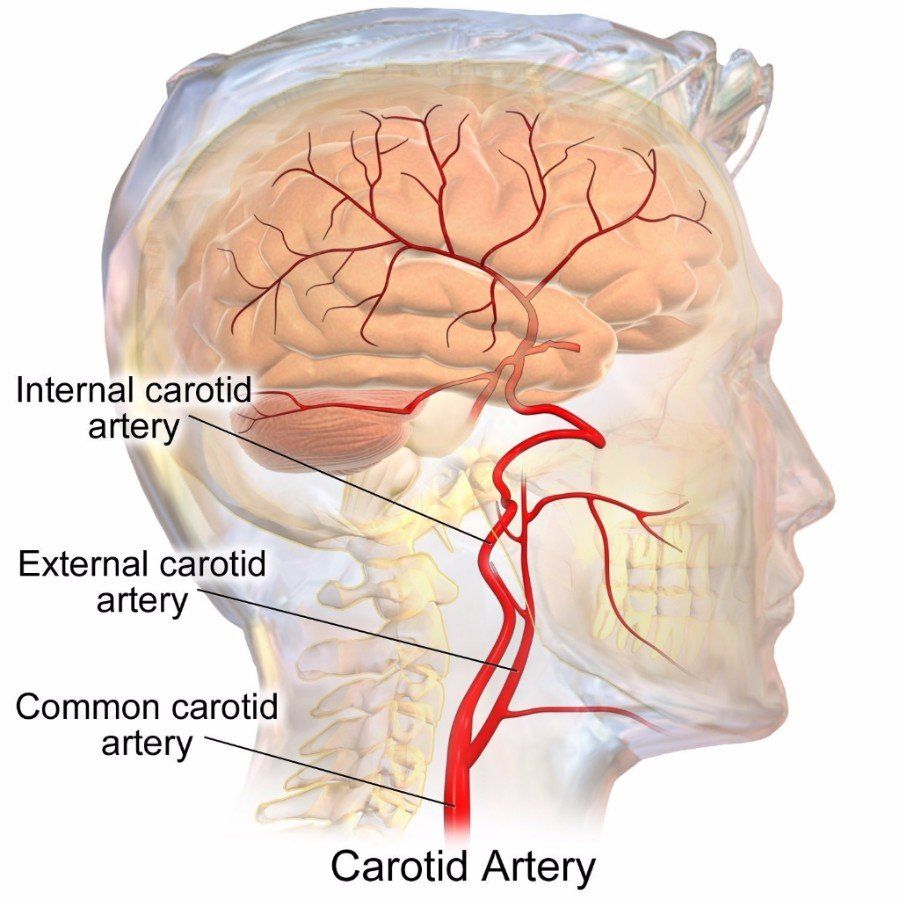

- There are two common carotid arteries located on each side of the neck that divide into the internal and external carotid arteries .

- The external carotid artery provides blood supply to the scalp, face, and neck.

- The internal carotid artery supplies blood to the brain and the retina.

- Vertebral arteries provides blood flow to the posterior circulation which supplies the hind brain i.e. brainstem, medulla oblongata, pons, vestibular apparatus, cerebellum and posterior cerebral cortex.

- Ischaemic signs occur more commonly in VAD than ICAD (>80%) but do

not present themselves until days or weeks (13).

Figure 1

(Blausen.com staff, 2014)

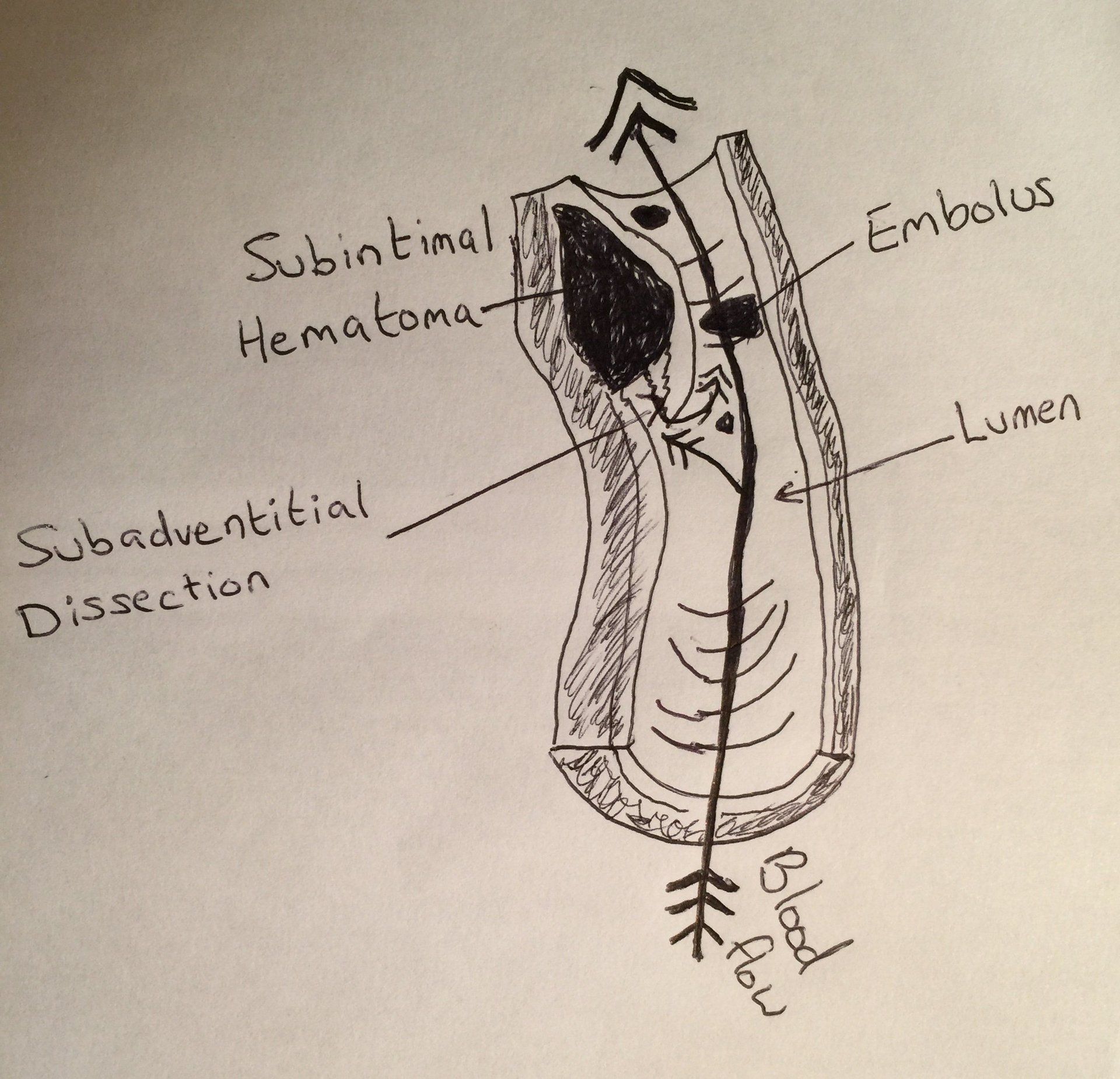

Carotid Artery Dissection (CAD) Pathophysiology

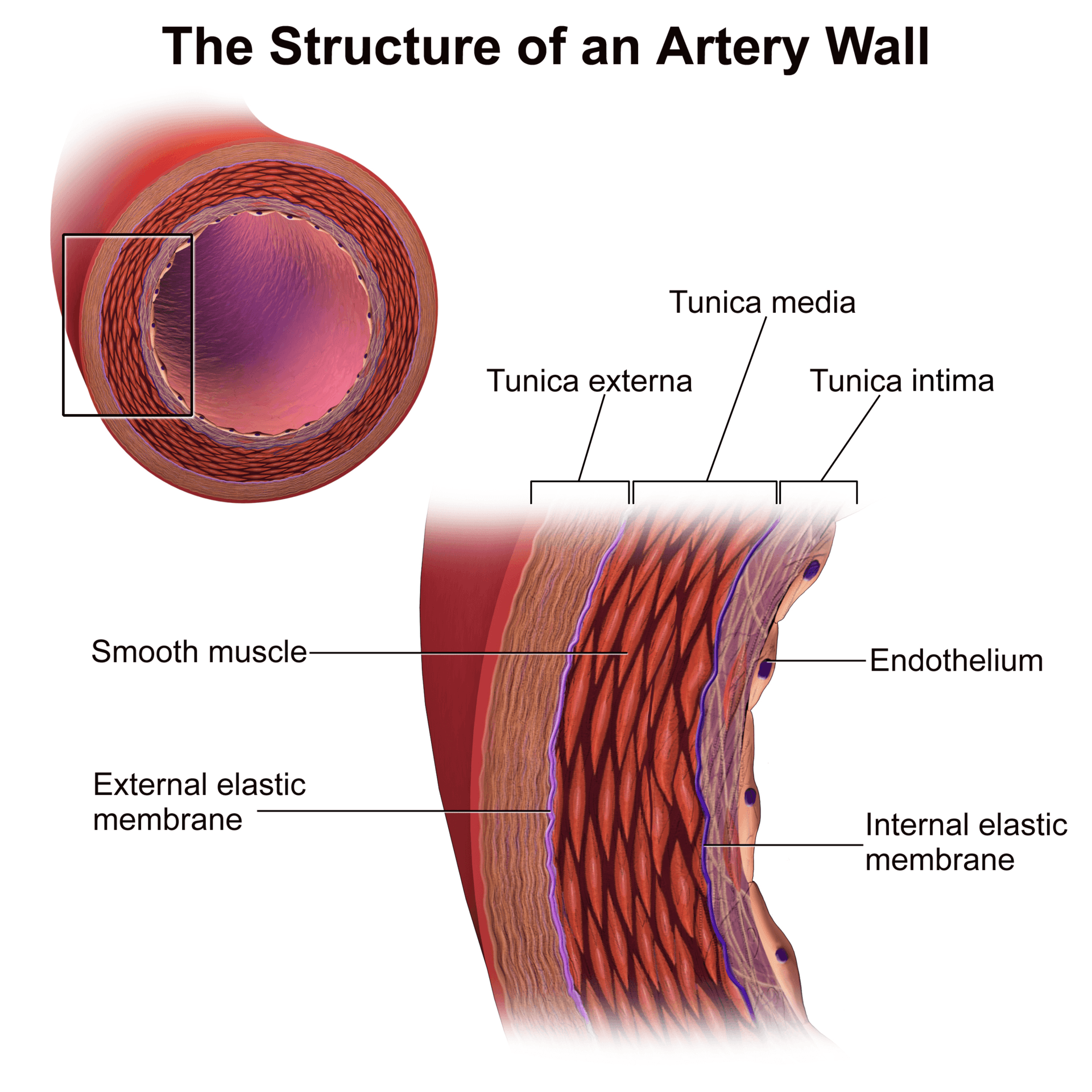

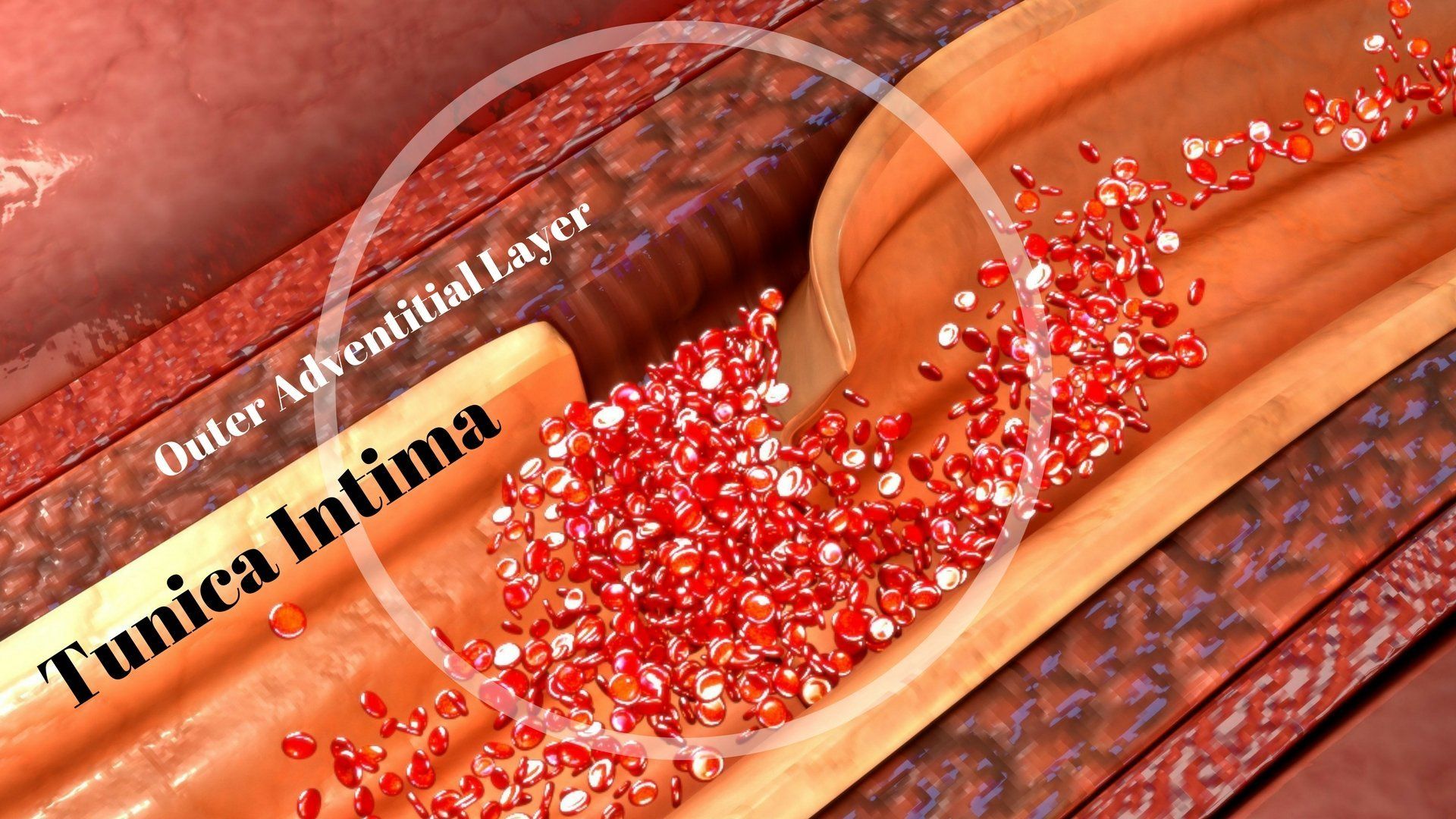

- Dissection of the vertebral and internal carotid arteries (ICA) usually arise from a tear of the inner wall (tunica intima) or outer adventitial layer (Figure 3).The anatomy of layers can be viewed in Figure 2.

- The creation of a pseudo aneurysm or degeneration of the media adventitial border results with the formation of micro hematomas and weakening of the vessel wall. This weakening is clinically significant, as the artery potentially has increased vulnerability during end range of cervical movement.

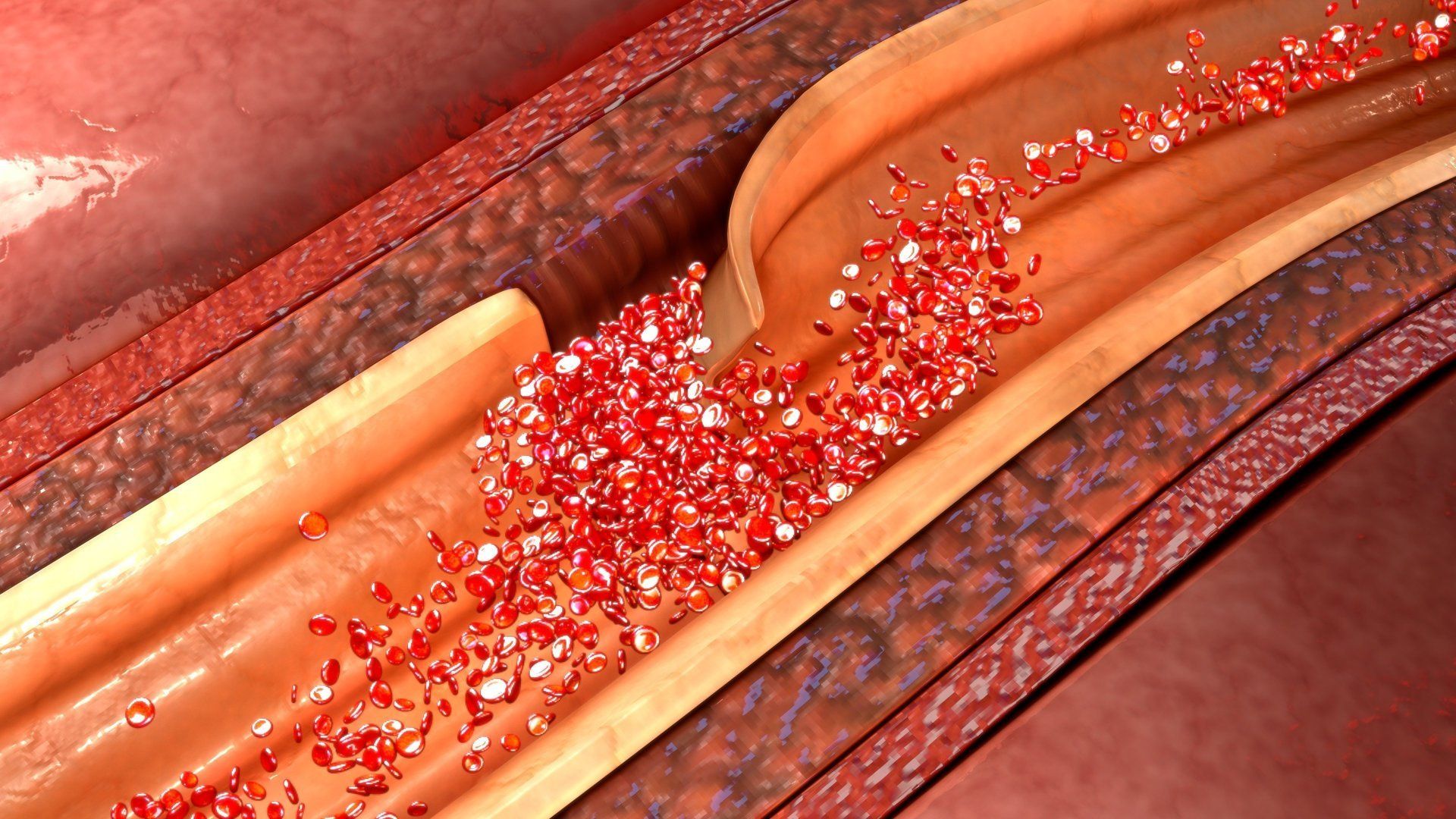

- Increased blood arterial pressure bleeding into a weakened wall enters the deep layers and can split the wall to form an intramural hematoma and cause swelling of clotted blood within the area (Figure 4).

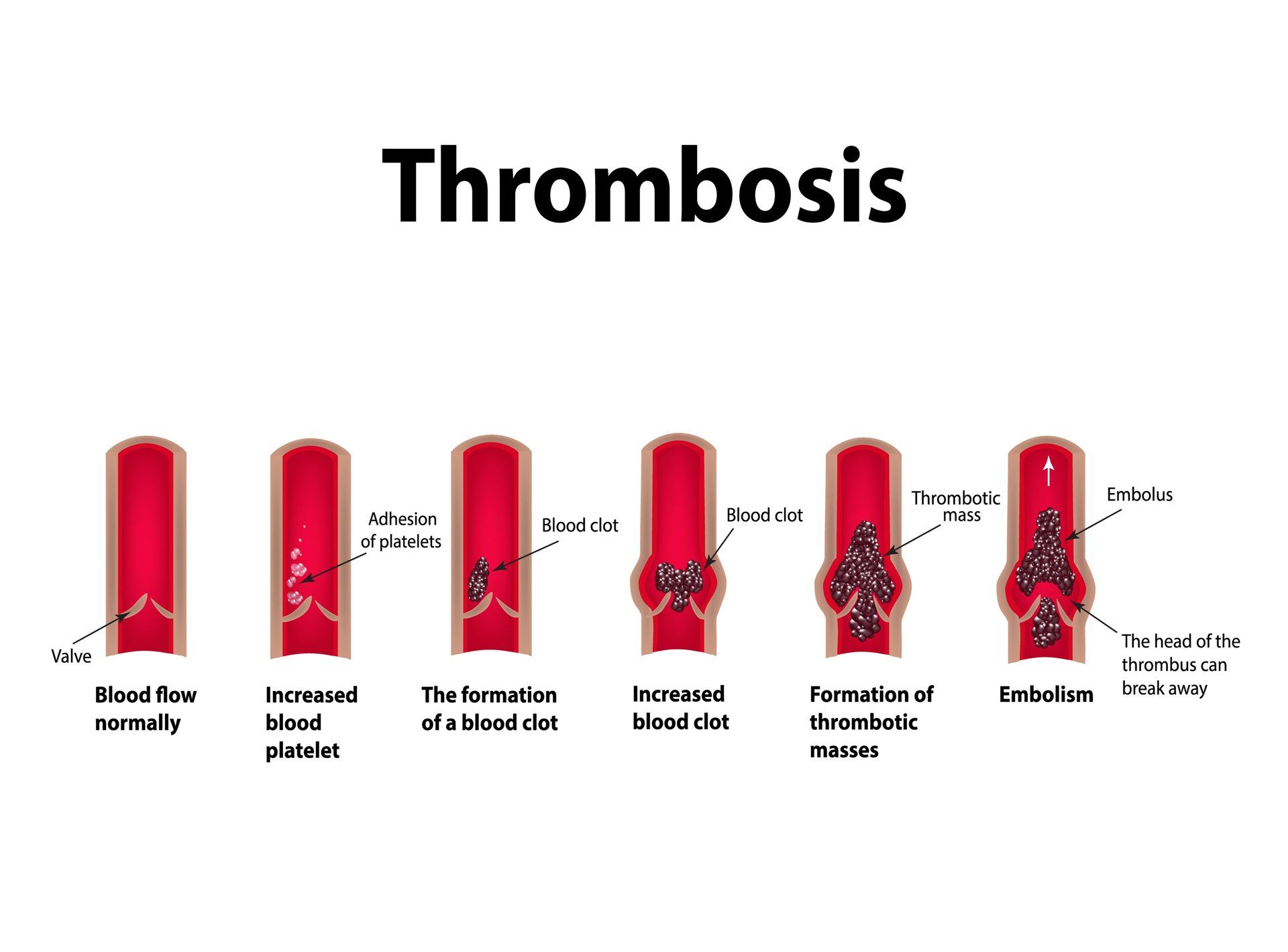

- This can cause a “dissection” of the artery and consequently alter the blood flow which may trigger the clotting cascade. An embolus may then break off and propagate to the brain causing an ischemic stroke (Figure 5) (16).

Figure 2: Medical gallery of Blausen Medical (2014 )

Figure 3

Figure 4

The diagram above (figure 4) shows a subadventitial dissection within the arterial wall and emboli detaching from a primary thrombus (inspired via Haneline and Rosner, 2007).

Figure 5

Is Carotid Artery Dissectiona Common?

Carotid artery dissection accounts for only 1-2% of all ischemic strokes, has been reported to occur in all age groups but most commonly between 35 and 50 years of age and slightly more frequently in men (16). In young and middle-aged people cervical artery dissection accounts for 10-25% of strokes and is the most reported adverse event and pathology of the cervical artery system (11, 17).

Vaughan et al., (2016) use the term cervical artery dysfunction which considers the internal carotid artery (ICA), the vertebral arteries, the vertebrobasilar system and the whole cervical arterial system.

Embolism from thrombus formation at the dissection site is thought to play a major part in stroke pathology.

Statistics: Annual incidence of Internal Carotid Dissection (ICAD).

- The annual incidence of internal carotid dissection (ICAD) is estimated at 2.5-3 per 100,000 people which is 0.00025% of the population (16).

- Estimates of CAD following a cervical manipulation at worst, range from 1 in 100,000 (0.001%) to in 1 in 6,000,000 manipulations (1, 10).

- The annual incidence of vertebral artery dissection (VAD) is approximately 1-1.5% per 100,000 or 0.001%, which is observed as lower than the incidences found from an ICAD (16).

What Are The Typical Symptoms of A Patient Presenting With A Carotid Artery Dissection (CAD)?

- Patients often present with at least two symptoms: unilateral head, neck or facial pain.

- Headaches experienced by the patient are typically in the fronto-temporal region and have been reported to present in the occipital region (17).

- Headaches might be described as a constant steady ache, throbbing or sharp in nature and commonly described by patients as unlike anything that they have ever experienced before (17).

- Smith et

al.

(2003) suggest how patients may seek spinal manipulative therapy (SMT)

in the presence of a pre-existing cervical artery dissection (CAD) which

presents as neck and/or head pain.

- Taylor and Kerry (2004) support the above and note a window of time when patients with an ICAD may present to the manual therapist with signs and symptoms that may mimic a neuromusculoskeletal (NMSK) presentation. Local signs and symptoms can precede cerebral ischemia (TIA or stroke) or retinal ischemia by anything from less than a week to beyond 30 days (9).

- Similar to Vertebral Artery dysfunction, headache and/or cervical pain can be the sole presentation of Internal Carotid Artery dysfunction, particularly in the early stages of pathology (9).

- Carotid arteries supply anterior cerebral circulation and ischemic symptoms of general stroke such as limb weakness, paraesthesia and speech disturbances may result if there is a progression (16).

- Ischaemic signs occur more commonly in VAD than ICAD (>80%) but tend not to present themselves until days or weeks later (13).

- The above should highlight how subtle clues obtained during a patient’s medical case history can alert clinicians to diagnose a potential vascular pathology and encourage appropriate decision making with regards to management and further referral.

- Cranial nerve palsies and Horner’s syndrome are often the result of Internal Carotid Artery pathology, especially if the onset is acute (8).

- All cranial nerves, except the olfactory nerve conveying the sense of smell, can be affected.

- The hypoglossal nerve (CN XII, tongue movement) is the most commonly affected out of all cranial nerves, followed by the glossopharayngeal nerve (CN IX, oral sensation, taste, and salivation). Vagus nerve (CN X), damage may include a rise in blood pressure and heart rate, hoarse voice, difficulty swallowing and loss of parasympathetic innervation to numerous structures. The accessory nerve (CN XI) might also be affected.

- Horner’s syndrome has been reported in approximately 33% in CADs and 14.3% in VADs. Symptoms include ptosis, miosis, and facial palsy and could be due to increased pressure on the sympathetic fibers from the enlarged I.C. artery (17).

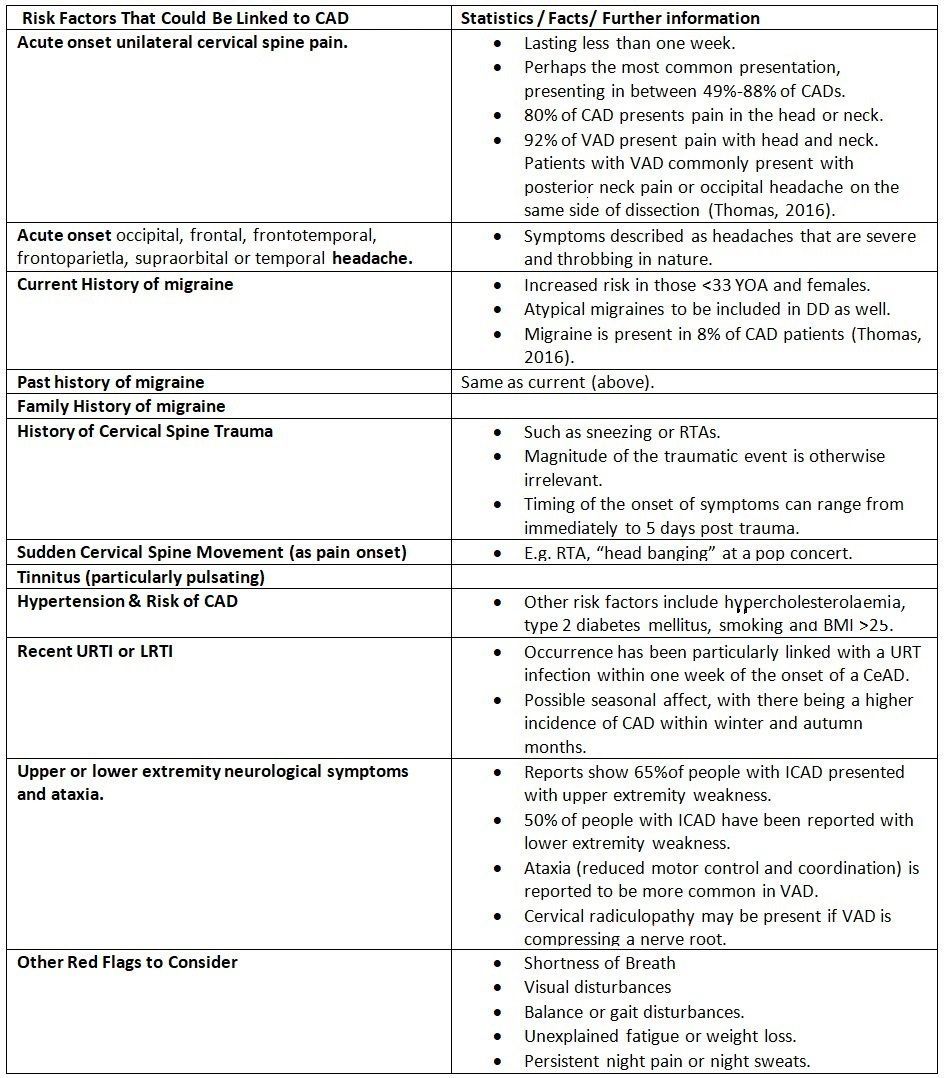

Case History Risk Factors For CAD (inspired via Vaughan et al., 2016):

Table 1 (Vaughan et al., 2016)

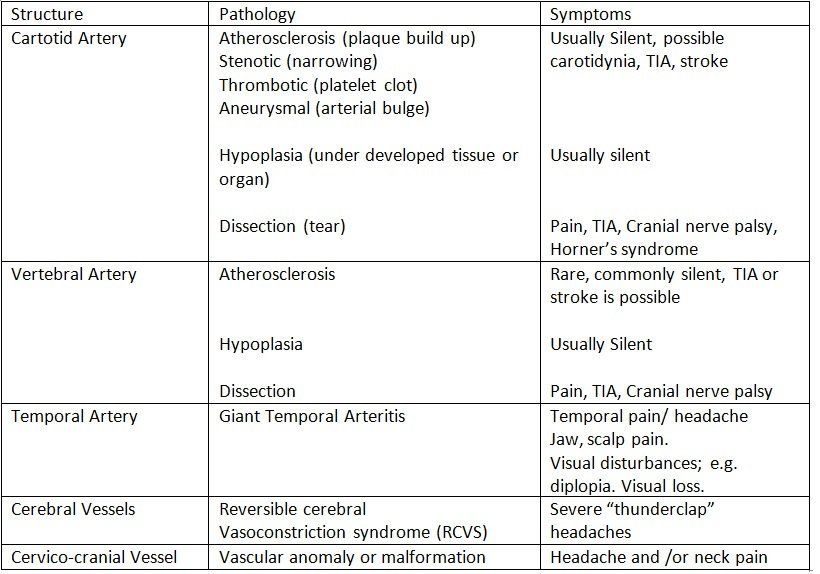

Kerry and Taylor (2014) sub divided patients' symptoms and pathologies via the following;

Table 2

Other risk factors to consider and have not been mentioned include; a recent infection, anticoagulant therapy, long term use of steroids, recent infection and blood clotting disorders.

Manipulative Therapy and Stroke

It is possible that stroke following cervical spine manual therapy might be associated with pre-existing vascular pathologies and an already present arterial dissection could further damage the artery or propagate an embolus.

Thomas (2016) suggest four mechanisms that could implicate the aetiology of CAD from cervical spine manipulation;

(i.)Force of the manipulation.

(ii.Manipulative therapy in the presence of a CAD.

(iii.)Positioning of the cervical spine during a manipulative maneuver causing an alteration of blood flow in the craniocervical arteries.

(iv.)A suggestion of manipulative thrust causing Vasospasm or arterial spasm leading to vasoconstriction, thus temporarily altering blood flow to the brain. Note, this has never been demonstrated in vivo (in the living).

Studies investigating occlusion of the cervical arteries suggest that head and neck positioning during an HVLA thrust has little impact on vertebral artery or internal carotid arterial (ICA) flow (17). The duration of arterial occlusion during Cervical HVT technique application is approximately 100-500ms and insufficient enough to affect blood flow to the brain (17).

Studies have investigated whether the amplitude of force for spinal manipulations could create a CeAD (cervical artery dissection) by applying the techniques to dogs and pigs, whose cervical artery structure are similar to humans (16, 20). Interestingly, the researchers concluded that they were unable to produce sufficient forces to cause any arterial damage (16). The same was concluded in cadaver studies which found that much greater forces were required to cause any damage to a normal artery (16, 19).

Authors have concluded that it is not the ‘‘thrust’’ that is dangerous but rather, extreme ranges of movement (14, 15). This theory is supported to some extent by numerous case reports of arterial dissection following visits to the hairdresser, performing yoga, ceiling painting, stargazing, and archery (21, 14).

Most episodes of a CAD can mostly be prevented via a detailed case history and a thorough clinical examination. Case reports have identified patients experiencing a CAD despite pre-manipulative screening tests which suggest that CAD is idiosyncratic with being unique to each individual and certain incidences difficult to predict (9).

Is VBI or Pre-Screening CAD Testing Reliable?

Abnormal stress on the vertebral artery may cause a reduction of blood supply to specific parts of the hindbrain, which is referred to as vertebrobasilar insufficiency (VBI) (8). Symptoms of VBI include dizziness, drop attacks, diplopia, dysarthria, dysphagia, ataxia, nausea, numbness and nystagmus. VBI can develop a cerebral or brain stem ischemia, leading to severe morbidity or even death (2).

The aim of pre-manipulative vertebrobasilar testing is to evaluate the adequacy of blood supply to the brain by compressing the vertebral artery and examining for the onset of signs and symptoms of cerebrovascular ischemia (7).

A report by Hutting et al., (2013) found that VBI testing sensitivity ranged between 0 and 57% and test specificity ranged between 67 and 100%. The systematic review concluded that it was not possible to draw a firm conclusion on the diagnostic accuracy of manipulative tests as a result of the large variances in ranges (8). Kerry and Taylor (2014) also concluded the same with that VBI and related testing to predict adverse events related to CAD are poor and have insufficient clinical value.

What Must Clinicians Do If They Suspect A CAD?

- Time is the most important factor if a CAD is suspected and the patient should be referred immediately to the nearest emergency department for further medical screening.

- Clinicians are to communicate via letter specific concerns about the possibility of CAD, identify key points of suspicion, for example; recent/ acute onset, unusual or idiopathic neck pain or a headache, any recent exposures to trauma, the need for further investigative imaging i.e. CT or magnetic resonance arteriography (MRA) .

- PRACTITIONERS BEWARE: there have been case reports when patients have attended emergency departments preceding dissection but were sent home without medical imaging evaluation, only to then return at another time after having experienced an ischemic event (5).

Case Study Report Example of CAD (Taylor and Kerry, 2005)

- 51 YOA Male, physiotherapist sneezed several times whilst the neck was left rotated. Afterwards, experienced left- sided mid-upper cervical spine pain and ‘‘aching’’ within the left temporomandibular joint and mandible region.

- On waking next day, ongoing symptoms included pain in the left sub-occipital region and difficulty during left cervical spine rotation with general left-sided headache at the left frontal region and eye.

- Symptoms remained constant with an estimated VAS of 6/10 and continued throughout the day and the next 48 hours required analgesia/NSAIDS. 48 hours later he experienced ptosis (drooping) of the left eyelid and constriction of the pupil on the left side. He realised that he had developed Horner’s Syndrome.

- The patient consulted his GP, who discussed the case with a Professor of Neurology. It was suggested that there might be a possible dissection of the carotid artery. He was advised to monitor his symptoms and call back urgently if there were any alterations in symptoms, particularly to any signs of transient ischaemic attack (TIA).

- He presented to the local accident and emergency department, an ultrasound scan (US) and a CT scan failed to confirm the clinical diagnosis.

- He was admitted for one night and prescribed Warfarin and Clexane. A diagnosis of ICAD was eventually confirmed by magnetic resonance arteriography (MRA) 2 weeks post injury and a management plan of further anticoagulation (Warfarin combined with Aspirin 300 mg) was prescribed.

- He was advised to rest from work for (6 weeks) and exertion with the increased risk of embolisation. One month after the onset of the symptoms the patient was still in considerable discomfort and had developed paraesthesia in the occipital region and a sensation of a ‘‘brittle feeling’’ as if ‘‘something was about to break’’. He still required NSAIDS to manage the symptoms. In addition he had become aware of pulsatile tinnitus , which was ascribed, by the vascular specialist, to the formation of collateral circulation in the external carotid.

- The patient was monitored with Duplex ultrasound and regular blood tests over a 12-month period. He returned to work 6 weeks after the onset of his symptoms.

- The pain and Horner’s’ syndrome partially resolved over the next 12 months, although the patient still reports mild ptosis and intermittent transient pain in the cervical/carotid and frontal region. The pain appears related to pressure on the supraclavicular region or effort of the upper limb and shoulder girdle.

- The patient has a clear PMH and FH for vascular disease. He did make the observation that as a postgraduate physiotherapy tutor he had spent a number of years teaching practical cervical treatment techniques involving varying degrees of cervical range of motion to end range.

- Prior to injury, he had suffered an undiagnosed problem of right-sided upper limb and hand fatigue and discomfort for a number of years, associated with playing a percussion instrument.

- Later examination of the right side revealed blanching of the hand associated with prolonged effort during function. A further interesting feature of the case was the development of symptoms of paraesthesia and discomfort on the right side of the head some weeks post initital injury. These symptoms were investigated and though unexplained by the vascular consultant, they were thought not to be related to the arterial dissection. Symptoms were treated successfully with manual therapy and eventually resolved.

Conclusion

Carotid Artery Dissection (CAD) is a topic that needs to be approached respectfully and with great care. As Kerry and Taylor (2014) highlight, such questions "does manipulation cause stroke?" can be viewed as unnecessary and uninformative. Manipulation applied to the cervical spine as a risk factor is more likely to be related to the cervical spine movement rather than manipulation itself (17).

One can conclude that episodes of a CAD in most incidences can be largely prevented by taking a detailed case history and a thorough clinical examination. Descriptions of subtle signs and symptoms from patients are significant sources of information for all manual therapists, encouraging professionals to make an appropriate clinical decision to prevent adverse events from ever happening. VBI or premanipulative screening and testing seems to have no clinical value

and suspicions of a CAD should be referred in writing for a magnetic resonance arteriography (MRA)

.

References:

1. Albuqerque, F. C., Hu, Y.C., Dashti, S.R., Abla, A. A., Clark, J. C., Alkire, B., Theodore, N., McDougall, C.G. (2011) Craniocervical Arterial Dissections as Sequelae of Chiropractic Manipulation:Patterns of Injury and Management . Journal of Neurosurgeons; 115 (6): 119-1205.Medical gallery of Blausen Medical (2014 ) WikiJournal of Medicine 1 (2).

2.

Asavasopon, S., Jankoski. J., Godges, J. J. (2005) Clinical Diagnosis of Vertebrobasilar Insufficiency: Resident’s Case Problem

. J. Orthop Sports Phys Therapy;35(10):645e50

3 . Bin Saeed, A., Shuaib A., Al-Sulaiti, G., Emery, D. (2000) Vertebral Artery Dissection: Warning Symptoms, Clinical Features and Prognosis in 26 patients . Can J Neurol Sci; 27: 292-6.

4.

Gössel, M., Rosol, M., Malyar, N. M., Fitzpatrick, L.A., Beighley, P.E., Zamir, M., Ritman, E.L. (Jun 2003). "Functional anatomy and hemodynamic characteristics of vasa vasorum in the

walls of porcine coronary arteries".

The Anatomical Record Part A:

Discoveries in Molecular, Cellular, and Evolutionary Biology

. 272

(2):

526–37.

5. Grond-Ginsbac, C., Metso, A., Metso, T., Pezzini, A., Tatlisumak, T., Hakimi, M. et al. (2013) Cervical Artery Dissection Goes Frequently Undiagnosed. Med Hypotheses; 80: 787-90.

6.

Haneline, M. T., Rosner, A. L. (2007) The Aetiology of Cervical Artery Dissection,

J. Chiropractic Medicine, 6:

pp. 110-120.

7.

Hutting, N., Verhagen, A. P., Vijverman, V., Keesenberg, M. D., Dixon, G., Scholten-Peeters, G. G. (2012) Diagnostic Accuracy of Premanipulative Vertebrobasilar Insufficiency Tests: A Systematic Review.

Man Ther; 18: pp. 177-82.

8. Kerry, R., Taylor, A. J. (2006) Cervical Arterial Dysfunction Assessment and Manual Therapy . Man Ther; 11(4): pp. 243-53.

9. Kerry, R., Talyor, A. J., Mitchell, J., McCarthy, C., Brew, J. (2008) Manual Therapy and Cervical Arterial Dysfunction, Directions for the Future: A Clinical Perspective , Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy. Vol. 16; 1: pp. 39-48.

10. Lee. K., Clarlini, W. G., McCormick, G. F., Albers, G. W. (1995) Neurologic Complications Following Chiropractic Manipulations: A Survey of California Neurologists , Neurology 45: 1213-5.

11. Marcus et al. (2015) Antiplatelet Treatment Compared with Anticoagulation Treatment for Cervical Artery Dissection (CADISS): a Randomised Trial , Lancet Neural; 14: pp. 361-67.

12. Medical gallery of Blausen Medical (2014 )". WikiJournal of Medicine 1 ( 2 ). DOI : 10.15347/wjm/2014.010. ISSN 2002-4436. - Own Work .

13. Silbert, P., Mokri. B. Schievinck, W. (1995) Headache and Neck Pain in Spontaneous Internal Carotid Artery Dissection . Neurology;45: pp. 1517-22.

14.

Taylor, A. J., Kerry, R. (2005) Neck

pain and Headache as a Result of Internal Carotid Artery Dissection:

Implications for Clinicians

. Man Ther; 10:73–77.

15. Terrett, A. G. J. (2000) Vertebro basilar stroke following spinal manipulation. In:Murphy DReditor. Conservative Management of Cervical Spine Syndromes. New York:McGraw-Hill; pp. 553–77 chapter 22.

16. Thomas, L. C., (2016 ) Cervical Arterial Dissection: An Overview and Implications for Manipulatie Therapy Practice , Manual Therapy, Elseiver; 21: pp. 2-9.

17 . Vaughan, B., Moran, R., Tehan, P., Fryer, G., Holmes, M., Vogel, S., Taylor, A. (2016) Manual Therapy and Cervical Artery Dysfunction: Identification of Potential Risk Factors in Clinical Encounters ; IJOM: 21: pp 40-50.

18.

WikiJournal of Medicine

1

(2). DOI

: 10.15347/wjm/2014.010. ISSN

2002-4436. -Own work.

19. Wuest, S., Symons, B., Leonard, T., Herzorg, W. (2010) Preliminary Report: Biomechanics of Vertebral Artery Segments C1-C6 During Cervical Spinal Manipulation , J. Manip. Physiol. Ther, 33; pp. 273-8.

20. Wynd, S., Anderson, T., Kawchuk, G.N. (2008) Effect of Cervical Spine Manipulation on A Pre-existing Vascular Lesion Within The Canine Vertebral Artery. Cerebrovascular Dis.; 26: pp. 3049.

21

. Zetterling. M., Carlstrom. C., Konrad, P. (2000) Internal carotid artery

dissection.

Acta Neurological Scandinavia 101: pp. 1–7.