Assessment & Treatment Management

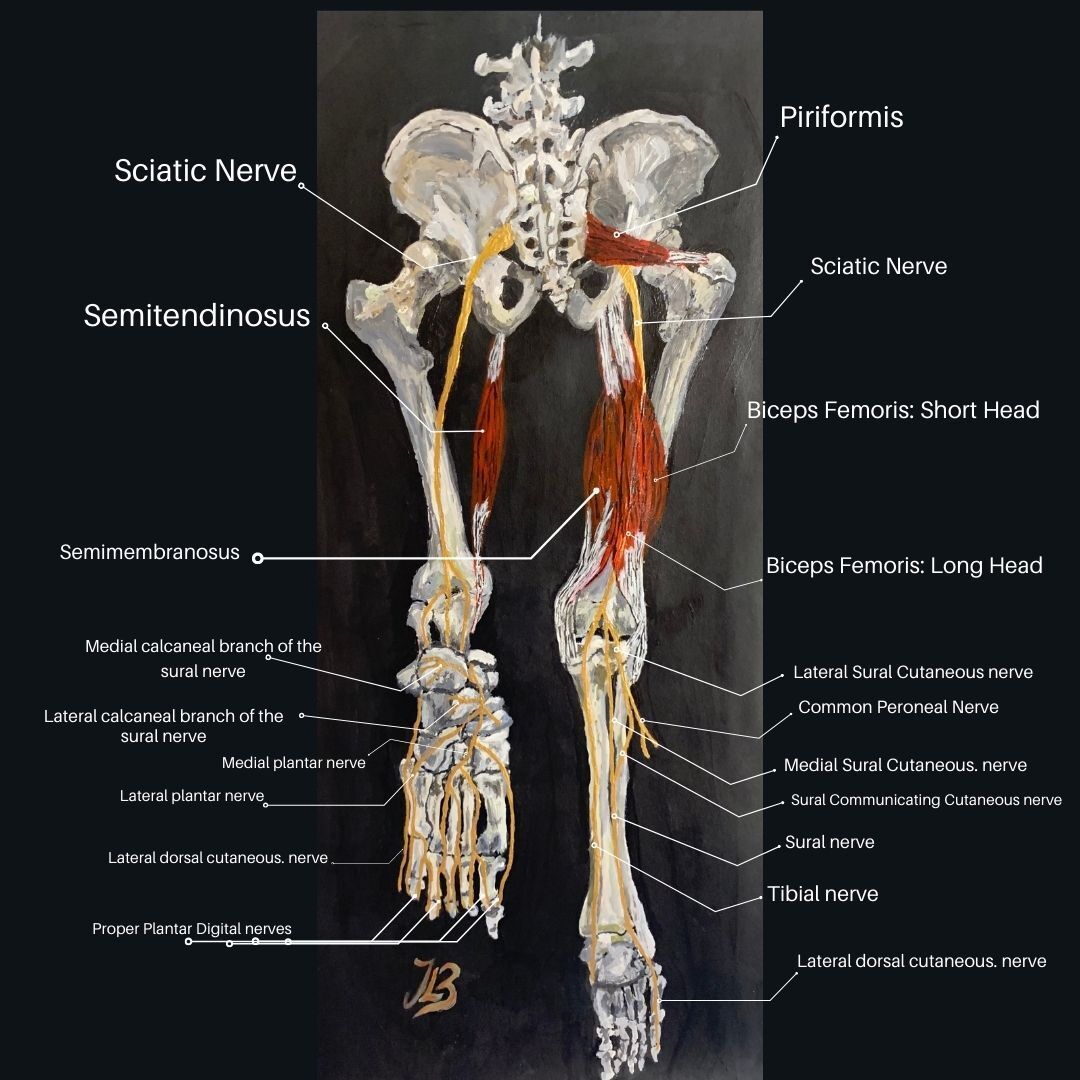

Figre 1. Anatomy of the hamstring muscles and posterior view of the sciatic nerve within the lower limb

Hamstring related injuries are commonly known to be associated with individuals who participate in sport and according to Ahmad et al.,

(2013) they account for approximately 29% of all sporting related injuries. Further statistics have included hamstring strains to make up around 50% of muscle injuries in sprinters, are most commonly found in hurdling and have an immense reinjury risk of 12% to 31%.With this rate of a reinjury, it is not surprising that there is so much information out there on hamstring strains and injuries (1).

However, severe hamstring muscle tightness can also be found in individuals who do not participate in sport.

All be it, hamstring tightness is frequently associated with lower back pain related disorders. But, hamstrings are crucial for postural control and everyday activity, it is little wonder that they are discovered to be taught in the majority of cases and can lead to sciatic nerve irritation.

In my previous years of practise, I have came across and treated individuals with a hamstring condition who have worked in several trading industries such as; construction workers, gardeners, landscapers, postmen and women, carpenters, farmers, roofers, scaffolders, tilers, road workers, brick layers, electricians, window fitters, welders, cooks, hairdressers and plumbers; the list goes on.

Desk bound office workers who find themselves prolonged sitting for many hours during the day also commonly gain tight hamstring muscles due to long hours of being stuck in a seated position in front of computer screens and endless meetings. It is time to discover the differentiation between a hamstring tear and proximal hamstring syndrome (or 'hamstring syndrome') and understand, study and analyse the 'why'.

Anatomy

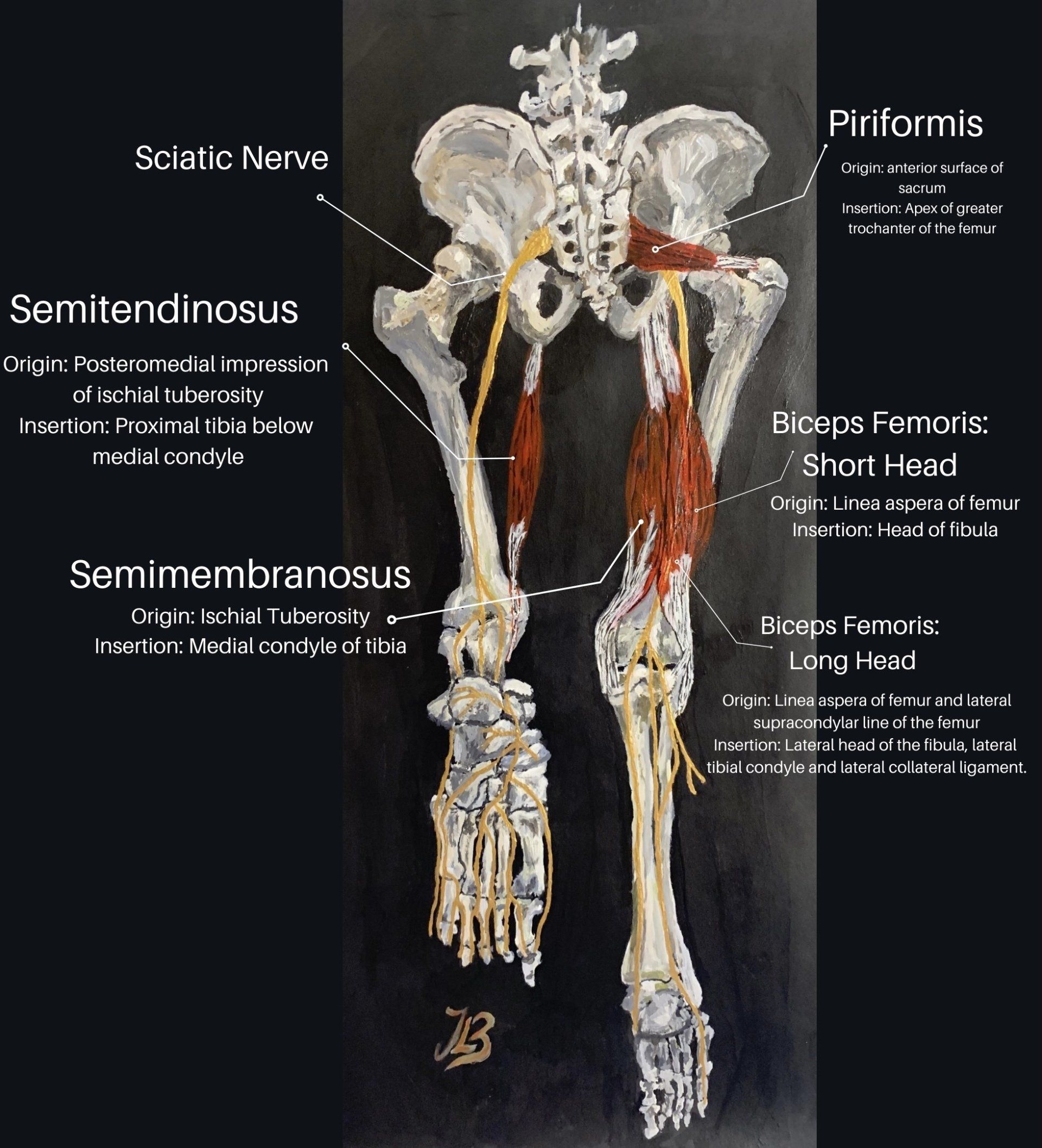

Figure 2. The origins and insertions of the hamstring muscles with the sciatic nerve

The hamstring muscles found at the back of the upper legconsist of three muscles which run all the way down the posterior thigh; semitendinosus, semimembranosus, and biceps femoris (long head) (5). Theyassist with bending the knee and extending the hip and play an important role in the performance of daily activities such as controlled movement of the trunk, walking, running, and jumping.

As mentioned previously, they are also important for maintaining balance and posture control whilst we stand. They significantly affect flexibility of the body, and taught hamstrings may result to reduced trunk stability and balance due to improper adjustment of the gluteus maximus and abdominal muscles (10). Inflammation of the tendons where they attach can lead to hamstrings tendinitis and injury is commonly seen in athletes and runners whose stride lengths are too long.

Figure 2 shows the posterior view of the sciatic nerve exiting the pelvis via the sciatic notch under the piriformis muscle and continues distally, lateral to the ischial tuberosity. In the proximal thigh, the long head of the biceps femoris crosses obliquely over the nerve (10).

From the posterior view, the sciatic nerve exits the pelvis through the sciatic notch under the piriformis muscle, then continues distally, lateral to the ischial tuberosity which is in close proximity before supplying the foot. In the proximal thigh, the long head of the biceps femoris crosses obliquely over the sciatic nerve.

Hamstring Muscle Strain Injuries

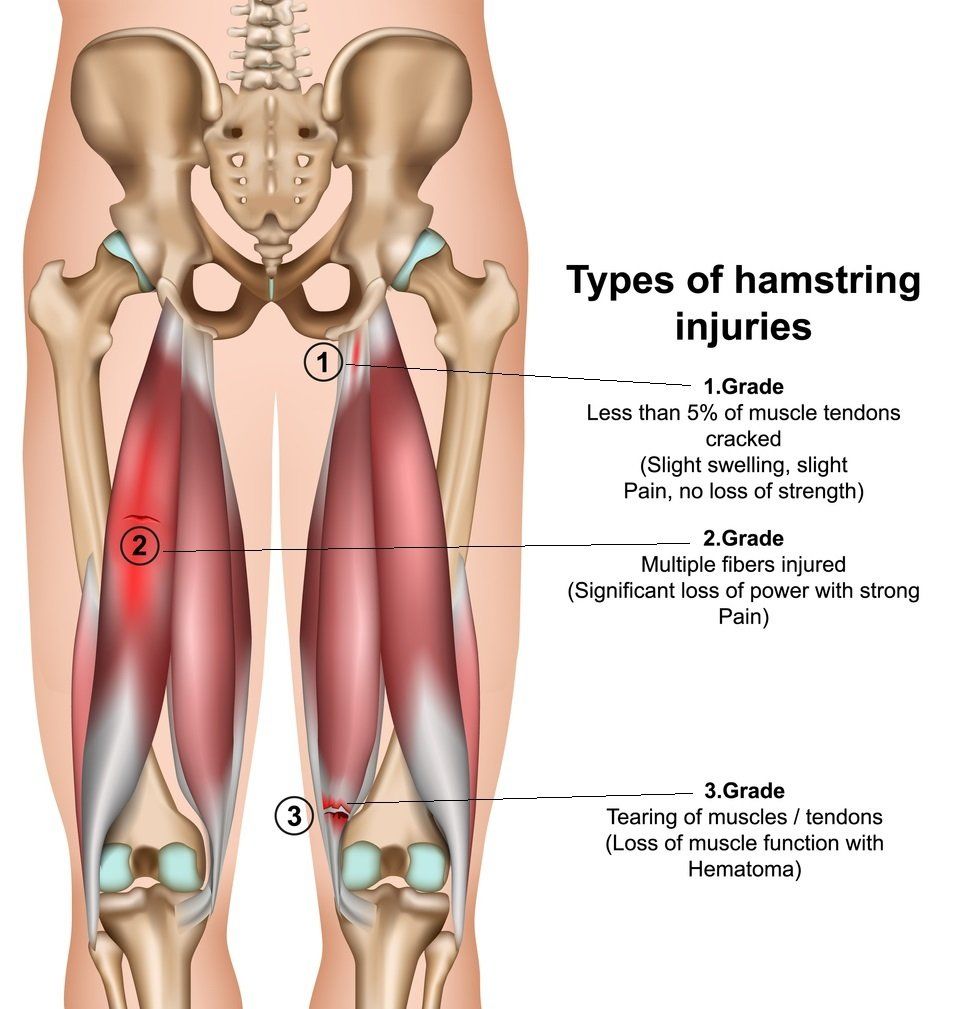

Figure 3. Types of hamstring injury

The clinical presentation of patients with a hamstring injury is related to the grade, location, and mechanism of injury (2).

Individuals who experience an acute hamstring strain injury will typically describe sudden onset of sharp, stabbing or twinge-like posterior thigh pain. Athletes or individuals performing a sudden vigorous activity may describe an audible “pop” which has been reported primarily in type II (overstretched) hamstring strains (2). The muscle strain usually stops them from continuing the activity or sport and they may present with a "stiff-legged" gait pattern to avoidsimultaneous hip and knee flexion (1).Chu and Rho (2016) explain how there are two main types of acute hamstring strains; Type I and Type II.

Type I Acute Hamstring Strain

Mainly occurs during high-speed running during the terminal swing phase of

running, when the hamstring muscles eccentrically contract to decelerate the swinging limb

and prepare for foot strike (3). The long head of the biceps femoris is most commonly

involved in this type of injury at the proximal muscle-tendon junction.

Type II Acute Hamstring Strain

Occurs during excessive lengthening of the hamstrings, are more common during activities such as dancing, slide

tackling and high kicking that combine hip flexion with knee extension(3). The proximal tendon of the semimembranosus,

close to the ischial tuberosity is mostly involved and recovery has been shown to

be prolonged compared to type I hamstring strains .

Proximal Hamstring injuries

Mild strains at this area of the hamstrings are less likely to seek medical

attention as their symptoms typically alleviate within a few days post injury.

Those who experience a moderate to severe injury typically describe a feeling or hear a 'pop' within the posterior aspect of the proximal thigh and hip area,

a tearing sensation associated with sudden onset of posterior thigh pain distal

to the ischial tuberosity with difficulty

weight-bearing. Within a few days after

the injury, patients usually notice the

presence of ecchymosis (bruising) over the buttocks

and the posterior aspect of the thigh which can extend down into the

leg(2).

Patients often have difficulty sitting

as a result of pain at the avulsion site and during the early phase of injury, walking can

be problematic for as long as four weeks with running being impossible to perform (2).

Some patients can also present with an

element of neuropathic posterior thigh

dysesthesia or abnormal sensations. This clinical presentation,

called gluteal sciatica, is related to compression of the sciatic nerve resulting

from hematoma (bruising) or scarring, the retracted tendon, or scarring and typically involves

mainly the posterior cutaneous branch

of the sciatic nerve.

Distal Hamstring Injuries

These can have a similar presentation to

that of patients with proximal injuries, as patients often report

weakness during in knee flexion as well as feeling a "pop" or snap in the posterior aspect

of the thigh associated with pain and

stiffness in the injured area which prevents

them from fully weight-bearing. Depending

on the degree of tear, patients may have a loss of active knee or hip flexion and in some cases may have difficulty with active extension. In patients with an isolated biceps

femoris rupture, pain can be localized

to the lateral or posterolateral aspect of

the knee (1). In addition, cramps and spasms

in the posterior aspect of the thigh are

not uncommon. Patients with chronic injuries

usually present because of profound

weakness rather than pain (1). In addition,

some patients present with gluteal sciatica symptoms due to excessive scarring

in the area of injury and subsequent

sciatic nerve tethering (1).

Physical examination

grading system:

Hamstring muscle strain injuries have traditionally been classified with

respect to their clinical presentation via a grading system with:

- Grade 1 = mild muscle strain, characterized by overstretching but minimal loss of the structural integrity of the muscle-tendon (1). The patient reports minor discomfort, minor swelling, no or a minimal loss of strength, and restriction of movement (5).

- Grade 2 = moderate strain having partial or incomplete tearing. The patient has marked discomfort and diminished ability to contract (5).

- Grade 3 = severe occurrence with complete muscle rupture. There is distinct pain and a total loss of muscle function (5).

- Grade 1 = muscle without fibre disruption.

- Grade 2 = muscle fibre disruption less than half the tendon or muscle width (a partial tear).

- Grade 3 = tendon or muscle disruption less than half its width witha complete disruption of the unit, including an avulsion injury from the ischial tuberosity (grade 3)(1).

Several authors, however, have tried to attempt predicting athletes' rate of recovery time before they can return to play or competition. Interestingly, proximal hamstring muscle injuries demonstrated a prolonged time to return to play (1). According to Ahmad et al., (2016), one study found that eighty three elite Australian rules football players with clinically diagnosed hamstring strains who had MRI features of a hamstring injury averaged 27 days missed from competition and those with no changes on MRI missed an average of 16 days (1).

Another classification system is based on the anatomical location of the injury, including (2):

- Proximal (injury of the tendon origin at the ischial tuberosity)

- Central (injury of the muscle belly, which is by far the most common pattern)

- Distal (injury of the distal musculotendinous insertion and tendons)

Mild strains at this area of the hamstrings are less likely to seek medical attention as their symptoms typically alleviate within a few days post injury. Those who experience a moderate to severe injury whilst participating in an activity typically describe a feeling or hear a "pop" in the posterior aspect of the proximal thigh and hip area, a tearing sensation associated with sudden onset of posterior thigh pain distal to the ischial tuberosity with difficulty weight-bearing (2,3). Within a few days after the injury, patients usually notice the presence of ecchymosis (bruising) over the buttocks and the posterior aspect of the thigh can extend down into the leg(2,3).

Patients often have difficulty sitting as a result of pain at the avulsion site. In the early phase of the injury, walking can be problematic for as long as four weeks and running is often impossible. Some patients can also present with an element of neuropathic posterior thigh dysesthesia (1). This clinical presentation, called gluteal sciatica, is related to compression of the sciatic nerve resulting from hematoma, the retracted tendon stump, or scarring and typically involves mainly the posterior cutaneous branch of the sciatic nerve (1,2).

AccordingChu and Rho(2016), patients with chronic proximal hamstring tendinopathy do not usually recall a specific inciting event, and report gradual increase of pain in the posterior thigh. The pain is often described as tightness or cramping in the posterior thigh or deep buttock, located close to or at the ischial tuberosity (3). Pain can extend down the posterior thigh distally to the popliteal fossa and symptoms can be exacerbated with repetitive eccentric hamstring contraction, forward flexion of the trunk and with running and pain whilst sitting (3).

Distal Hamstring Injuries

These can have a similar presentation to that of patients with proximal injuries. Patients often report weakness in knee flexion as well as feeling a "pop" or a snap in the posterior aspect of the thigh associated with pain and stiffness in the injured area that prevents them from weight-bearing. Depending on the degree of tear, patients may have loss of active knee or hip flexion and in some cases may have difficulty with active extension. In patients with an isolated biceps femoris rupture, pain can be localized to the lateral or posterolateral aspect of the knee (4,6,9). In addition, cramps and spasms in the posterior aspect of the thigh are not uncommon. Patients with chronic injuries usually present because of profound weakness rather than pain. In addition, some patients present with gluteal sciatica symptoms due to excessive scarring in the area of injury and subsequent sciatic nerve tethering (2,3,4).

Hamstring Syndrome

A serious complication of nonoperatively treated proximal hamstring injuries is "hamstring syndrome". According toSaikku et al., (

2010), the term "hamstring syndrome" was first brought about by an orthopadic surgeon, Dr Puranen, whopublished a report on a series of six surgically treated patients who had entrapment of the proximal sciatic nerve caused by fibrotic hamstring tendons (9).

This condition usually presents aslocal posterior buttock pain, persistent pain at the

ischial tuberosityand proximal hamstring regionsmade worse via sitting which may be associated to previous hamstring injury or tendinopathy (8, 9, 11). Pain may also be made worse by fast running and stretching or exercising the posterior thigh.

Hamstrings syndrome could be perceived as a neurologically associated condition, as its occurrence is mainly secondary to tendinous bands of the hamstring muscles entrapping or scarring around the sciatic

nerve from fibrosis of the injured

hamstring tendon (2, 9). This scarring

leads to tethering of the nerve, especially

with specific positions, including sitting

or positions (e.g. at work) that involve stretching the

hamstring muscles which may lead to sciatica related pain(2).

Proximal sciatic nerve entrapment via the hamstring fibrotic bands entrapping the sciatic nerve can irrevocably lead to the need of surgical intervention (10). Various authors have concluded that a complete neurolysis of

the sciatic nerve from adherent tissue was

an essential component for the need of operative

treatment (2,8,9).

Orthopaedic surgeons; Puranen and Orava(1998)reported successful results of surgical intervention after obtaining relief in 52 of 59 patients after the division of taught, fibrous bands of the hamstrings (9). They both developed the Puranen-Orava test to helpdiagnose proximal hamstring tendinopathywhich involves a standing test that actively stretches the hamstring when the hip is flexed to 90 degrees with the knee fully extended and the foot is on a support 90 degrees to the standing body(3,9).

Treatment Management, How Can Physical Therapy Help?

Hamstrings Stretch

The main purpose of any rehabilitation

program following nonoperative treatment of a hamstring

injury is to restore the preinjury level of

function and to control the pain and inflammation (2).

Physical Therapy

Single-tendon avulsions and 2 tendon tears with retraction of less than 2 cm are treated nonoperatively (1).

Three phases of rehabilitation for acute hamstring strains are usually followed with phase 1 focusing on decreasing pain and edema and preventing scar tissue formation (2,3).

Phase I

Initial management of hamstring strains in the acute phase includes the RICE protocol of rest, ice, compression and elevation along with NSAIDs.Athletes are encouraged to shorten their strides whilst walking and use crutches for more moderate or severe injuries (3). Trunk stabilisation exercises can be performed, but exercises should be performed within a limited and protected range of movement and isolated resistance or excessive stretching exercises of the affected hamstring muscle should be avoided (2,3). Progression to phase II may occur when the athlete is able to walk without pain, jog at very low speeds without pain and perform pain-free isometric hamstring contraction exercises with prone knee flexion at 90 degrees against submaximal resistance at 50–70% effort(1,2,3).

Phase II

Involves a gentle increase in intensity of activity and exercise to improve range of motion, introduce eccentric resistant exercises, and neuromuscular training at faster speeds. Exercises involve a gradual increase in range of motion and lengthening of the hamstrings. Hamstring lengthening to end range of motion is avoided as there is still weakness within the muscle during this phase(3).

Eccentric strengthening exercises for the hamstringsare initiated as they have been demonstrated to be effective treatment for tendinopathy (3). Progression to Phase III occurs when there is full strength of the hamstring without pain when performing 1 repetition of maximum isometric contraction with prone knee flexion at 90 degrees, and the athlete can jog forward and backward at 50% maximum speed without pain.

Phase III

At this stage, rehabilitation involves more advanced neuromuscular control and eccentric strengthening exercises and sport/ activity-specific exercises with the goal of returning the athlete/ individual back to play. Progressive ability and trunk stabilization exercises should incorporate more sport-specific drills and dynamic agility exercises. Eccentric hamstring strengthening exercises can be progressed toward end range of motion by e.g. using hamstring curl machines, reverse cable curls, weight bearing hamstring curls on exercise ball, reverse plank, kneeling Nordic leg curl, standing single or double leg dead lifts (3,4,10). Return to sport criteria include no pain with palpation over the injury site, full concentric and eccentric strength of the hamstrings without pain.

Other nonoperative physical therapy management methods may consist of medical acupuncture, electrotherapy e.g. ultrasound, electrical stimulation, rock tape and soft tissue massage along with prescribing exercises.Steroid Injections

Ultrasound-guided corticosteroid injection can be used to provide initial relief in up to 50% of patients at 4 weeks. An alternative to corticosteroid injections includes Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) therapy performed under computed tomography or ultrasound guidance, which has similar outcomes to corticosteroid in experienced hands. These injuries may take up to 6 weeks for initial healing. In single-tendon tears, 6 weeks allows the tendon time to fibrose to the intact tendons, often allowing the initiation of limited activity.

Operative Treatment

Operative treatment is recommended for acute proximal hamstring injuries in which all three hamstring tendons are avulsed from the ischial tuberosity. Acute injuries are easier to repair, and early repair has shown excellent functional results.Operative treatment is considered in cases of high-grade two tendon injuries with more than 2 cm of retraction, especially in athletes participating in sports requiring the maintenance of a seated position under eccentric loads to the hamstrings (e.g., waterskiing, rodeo, kite surfing) (2,3,10). The goal of treatment of these injuries is to restore muscular and osseous attachments. Several techniques have been described, and most involve the use of suture anchors for approximation of the muscular rupture or avulsion to the ischial tuberosity.

Operative intervention is usually considered for chronic injuries if the patient cannot return to his or her desired activity because of persistent weakness, pain, or both and nonoperative treatment efforts have not worked (2,3). Delayed operative repair of complete proximal ruptures has found to have worse postoperative strength, with the potential for sciatic nerve involvement by surrounding scar tissue formation.

Full return to sport should only be allowed once the patient is asymptomatic with regard to pain and strength has returned to a grade 1 of the contralateral leg.

Possible treatment modalities at the clinic can be viewed in the video below.

References

1. Ahmad, C. S., Redler, L, H., Ciccotti, M. G., Maffulli, N., Longo, U. G., Bradley, J. (2013) Evaluation and Management

of Hamstring Injuries

, The American Journal of Sports Medicine:

1-15.

2. Alzahrani, M. M., Aldebeyan, S., Abduljabbar, F., Martineau, P. A. (2015) Hamstring Injuries in Athletes:

Diagnosis and Treatment

, 3; 6: 1-11.

3. Chu, S, K., Rho, M. E. (2016) Hamstring Injuries in the Athlete: Diagnosis, Treatment, and

Return to Play

, Curr Sports Med Rep,15(3): 184–190.

4. Fatima, G., Qamar, M. M., Hassan, J. Ul., Basharat, A. (2017) Extended sitting can cause hamstring tightness , Saudi Journal of Sports Medicine, 17; 2:

5. van der Made. A. D., Wieldraaijer, T., Engebretsen, L., Kerkhoffs, G. M. M. J. (2014) Hamstring Muscle Injury, Acute Muscle Injuries: 27-44.

6. Martin. H, D. Khoury. A., Schröder, R., Palmer. I. A. (2016) Ischiofemoral Impingement and Hamstrings Syndrome Distal Causes of Deep Gluteal Syndrome, Clin Sports Med; 35: 469–486.

7. Martin, H. D., Shears, S. A., Johnson, C. J., Smathers, A. M., Palmer, I. J. (2011) The Endoscopic Treatment of Sciatic Nerve Entrapment/ Deep Gluteal Syndrome ; Arthroscopy, The Journal of Arthroscopic and Related Surgery, 27; 2: 172-181.

8. Parka, J., Chab, J., Kimb, H., Asakawa, Y.(2014) Immediate effects of a neurodynamic sciatic nerve sliding technique on hamstring flexibility and postural balance in healthy adults, Physical Therapy Rehabilitation Science, 3; 1: 38-42.

9. Puranen. J., Orava, S. (1988) The Hamstring Syndrome. A New Diagnosis of Gluteal Sciatic Pain , 16; 5: 517-521.

10. Saikku, K., Vasenius, J., Saar, P.(2010) Entrapment of the Proximal Sciatic Nerve by the Hamstring Tendons, Acta Orthopædica Belgica; 76: 321-324.

11. Vaghef, S. H. E., Samereh Dehghani Soltani1 , Abdolreza Babaee (2017) An Uncommon Anatomical Variation of the Sciatic Nerve , 14; 2: 97-100.