Modern day living has essentially lead to a sedentary lifestyle with us spending more of our time sitting. In fact it has been estimated that on average, adults generally spend up to as much as six to eight hours or 45-50% of our waking hours in one day in a seated position (18).

Questions regularly asked from physical therapists is how can our daily habit of staying seated at a desk for long periods affect our body posture and its function in the short and the long term.

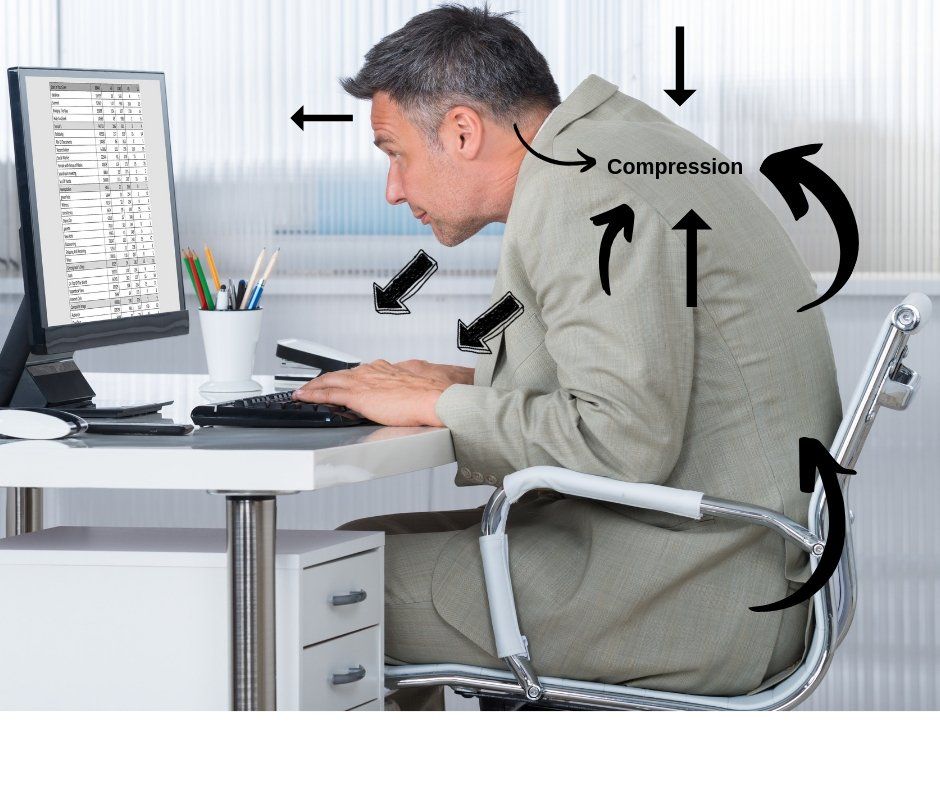

A short answer is that there is a growing causal relationship between prolonged sitting and lower back pain (LBP), as the positioning increases intra-discal pressure, stiffness of the lumbar spine (lower back), reduced strength of lower back muscles and a reduced metabolic exchange which can lead to excessive body weight (16).

More studies are showing that occupations that involve prolonged sitting have a high incidence of LBP and it is not surprising that back and pelvic pain are a common complaint amongst office workers in particular.

Because musculoskeletal (MSK) pains related to occupations are common in society, they are also referred to as work related musculoskeletal disorders (WMSDs). Symptoms are prevalent amongst workers involved in physical exertion work and sedentary work (4).

Sedentary work is defined as occasionally lifting no more than ten pounds, and sitting with occasional walking and standing. In occupational science, a static body posture is defined as a posture held for more than four seconds (15).

Various studies have investigated the effect of prolonged sitting, awkward posture and the repetitive motions that we put our bodies through on a daily basis related to WMSDs(4). But, there remains various gaps unfilled when it comes to finding a universal solution of how to lessen our joint aches and pains after a day's work in the office.

Lumbar Spine & Flexion

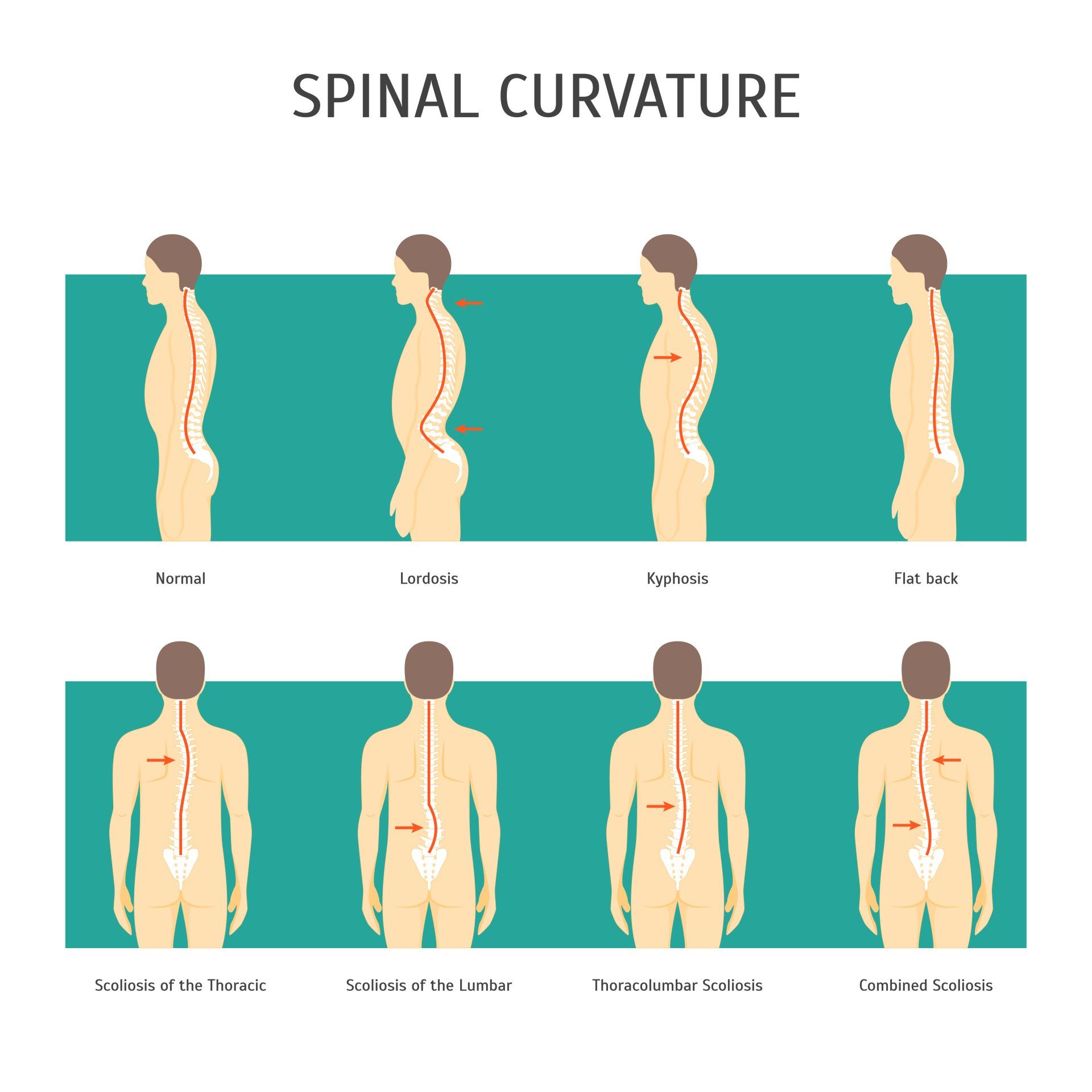

The link between back pain and seated work has been attributed to the required adoption of a flexed (bent forward) curvature of the lumbar (lower back) and thoracic (mid back) spines (6).

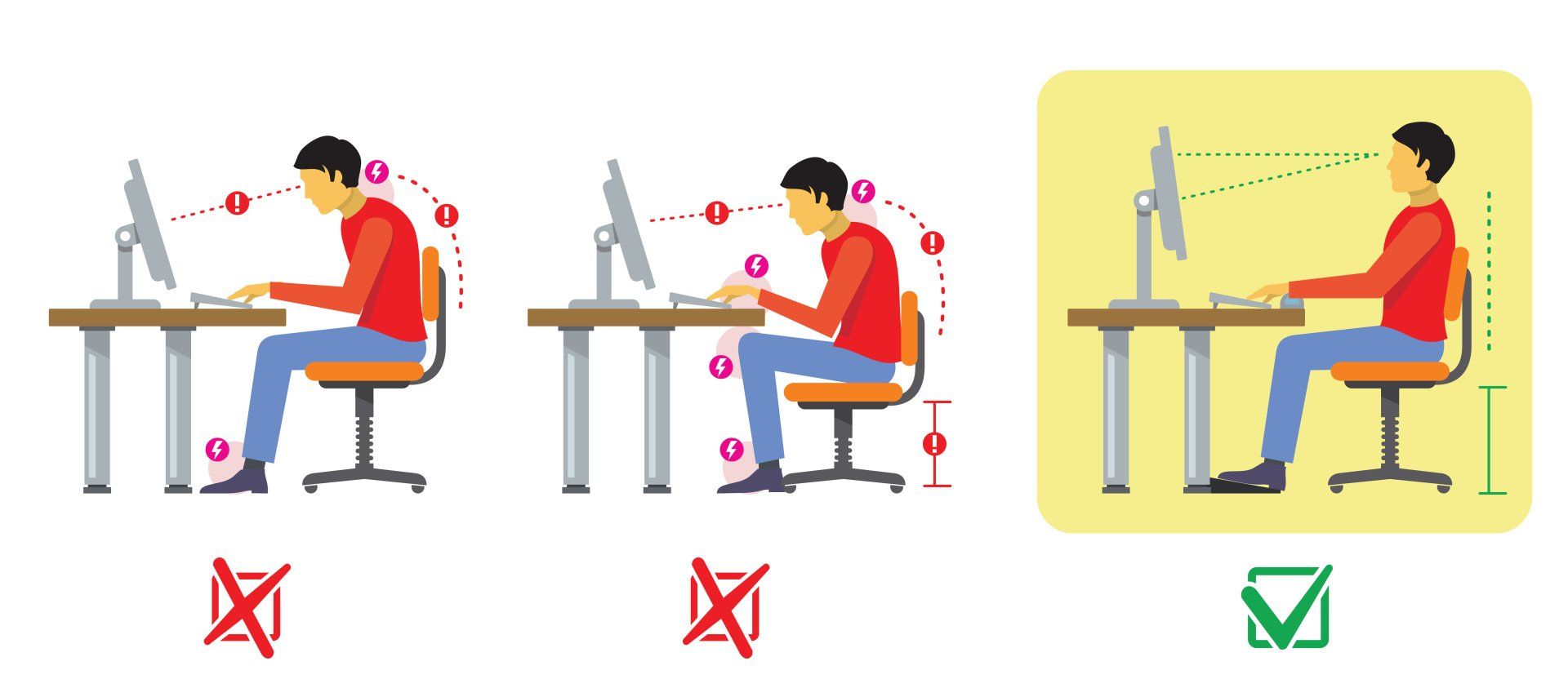

Body postural demands for seated tasks generally require an upright torso and a moderately flexed lumbosacral (LS) (very bottom of the back) spine (40-80%). Whilst sitting performing deskwork, we tend to adopt a flexed lumbar posture which increases on average by approximately 5 degrees over the course of a working day which is suggested to be as a result of ligament laxity via the discs narrowing from a loss of fluid content (2).

McGill and Brown (1992) found that residual creep-stretch within muscles and ligaments remains for a period of time after prolonged lumbar flexion whilst sitting or being in a slumped posture. This study’s main finding was that individuals who spend long periods of time sitting, especially in a slumped posture, and then suddenly go on to perform demanding heavy lifting activities within a short period of time after are at a greater risk of a hyperflexion injury to the disc and ligaments (21). For example, if a lorry driver, gardener, courier or warehouse shipper/receiver sit for long hours and are suddenly required to unload a truck, it is strongly advised to stand and walk for a few minutes prior to performing demanding manual exertions to avoid uneccessary injury.

The Impact of 'Creep' on Tissues

Creep is the progressive deformation of a structure within the vertebral column which has been under a constant load over time (26). The load placing stress on the area (of the vertebral column) is usually below the level required to cause complete tissue failure. But, during creep, the segments are usually at their maximum limited range of movement and the spinal column (or segment) will continue to deform in the direction of load (26). Sitting for long periods with the head protruded forward with a rounded upper back whilst typing at a desk will encourage both the neck and back to gradually be inclined to reside in this position.

Creep response in the vertebral column is thought to be caused by the gradual arrangement and increased stress placed on viscoelastic tissues which include collagen fibres, proteoglycans and water in the intervertebral discs, spinal ligaments and zygapophyseal joint capsules (26).

If individuals sustain a flexed lumbar spine posture whilst performing deskwork, the passive flexion stiffness (PFS) of the lumbar spine can reduce over time because of viscoelastic creep or stress-relaxation in the posterior lumbar tissues (3). Increased intervertebral joint laxity with sustained flexion loading can attribute to fluid loss in the intervertebral discs. Reduced PFS can increase the risk of a hyperflexion injury during instances whereby prolonged sitting is followed by tasks that involve full lumbar flexion (3). Beach et al., (2004) concluded that it can only take up to one hour of sitting for PSF to occur and increase the risk of injury if full flexion movements are attempted after.

The amount of axial compression and flexion creep increases with age, but the amount of creep depends upon the magnitude and direction of load application. The vertebral column does and can recover when the load is removed but at different rates. It is no surprise that as we grow older, the rate of recovery is slower and tissues take more time to heal (25). The difference in the loading and unloading of segments or the vertebral column is known as ‘hysteresis” (25).

A small scale study conducted by Oliver and Twomey (1995) suggests that brief periods of sustained extension loading within the lumbar spine during occupational activities, such as painting ceilings or undesired standing postures can cause significant creep to the viscoelastic tissues (mentioned above).

In disc height loss, associated creep in severe cases can lead to altered morphology of the neural foramina resulting to nerve impingement, which has been shown in an animal model to initiate pain with nerve root compression. More moderate cases of creep changes could create strains in the passive tissues in the intervertebral joint such as the disc or articular capsule sufficient to generate pain from compressive loading.

Sitting: Muscle Activity & Spine Mobility

Erect sitting with forward inclination of the upper body usually causes the highest level of muscle activity (23). Snijeders et al., (1995) found that individuals use a small level of oblique abdominal muscle activity when subjects are seated or stood during a stooped posture, but had strong activity when sitting in extreme flexion. They found limited or no activity in the erector spinae, gluteus maximus and biceps femoris muscles during erect postural sitting. The activity of the internal obliques was high whilst the external obliques showed moderate activity.

In passive sitting on an office chair with a hard seat and a back rest all muscles recorded showed little or no activity, except the internal and external obliques. Reduced oblique abdominal muscle activity tends to occur whilst sitting on a soft car seat if compared to sitting on a hard seat of an office chair (28)

Reduced thoracic mobility has been observed in individuals who spend more than 7 hours a day sitting and performing less than 150 minutes (2 ½ hours) of physical activity each week (17). This study found that there was a reduction of thoracic spine mobility by as much as 10% for individuals who sat for more than 7 hours per day and perform less than the recommended level of physical activity per week (2 ½ hours) (18).

It is also interesting to note that studies have found arm rests on chairs to reduce the level of actitvity of upper trapezius and neck muscles. A study on dentists found significantly reduced right sided anterior deltoid activity (by 68%) with the use of fixed arm supports whilst they were compared to working without arm supports (4).

Visser et al. (2000) studied the effect of using arm supports in visual display unit work on physical workload. They reported significantly lower levels of upper trapezius muscle activation when typing with the use of arm supports compared to typing with no arm supports.

Upright sitting (i.e. neutral posture) is associated with high muscle activity, which during prolonged sitting has been associated with muscle fatigue and pain (18). Conversely, slump sitting has been associated with increased spinal loading from the body tending to posteriorly tilting the pelvis which is then counterbalanced by excessive contractions of the dorsal spinal muscles (17). Slump sitting has also been associated with greater head/neck flexion, anterior translation of the head and increased cervical erector spinae muscle activity in comparison with upright sitting (8).

Do Different Postures Suit Certain Office Chairs?...

Sitting Vs Standing For The Spine

According to Leivseth and Drerup (1997), our bodies respond differently when we are sitting relaxed to when sitting at a desk and concluded that spinal loading whilst working in a sitting position is higher than spinal loading in a relaxed sitting posture (18). Another study concluded that spinal loading during work in a sitting position is higher than spinal loading in a relaxed sitting posture (19).

Patients with chronic lower back pain have been found to demonstrate poorer postural control of the lumbar spine than healthy individuals along with a pelvic asymmetry which creates further changes to soft tissue tightness (Akkarakittichoke and Janwantanakul, 2017).

During standing, research has shown that compressive loads on the lower back is minimal, however, prolonged static standing has been associated to the reporting of lower back pain and disc height loss (15).

Certain jobs such as cashiers, bank tellers and casino dealers spend a majority of their workday standing. These roles tend to lead the worker adopting awkward postures, reduced trunk motion and increased repetitive upper extremity tasks (15).

Sitting in a neutral position is not necessarily the "ideal" sitting position...

What Is Considered A Good Chair ?

Springer (2010) has a rather modern approach with how seating should be with relation to spinal biomechanics by fundamentally

asking future ergonomic seating arrangements to consider ‘what should

a chair do?’

1.) Support a person’s body as an individual - As explained above, accepting that we all have different body types, shapes and sizes, the design of a chair needs to accommodate the range of individuals who will be using it.

2.) Support activity – When considering task seating, what people do, how they do it and for how long are essential pieces of information. Chairs should support all the activities in which people engage, not just one primary activity.

3.) Promote movement – A chair should promote movement and encourage the natural movements of the body as it provides support. Movement should not require conscious effort. Chairs should move with the user, and make it easy to move (13).

4.) Enable performance – An ergonomic office chair should facilitate, support and enable effective performance.

5.) Be easy to use – adjustments made must be simple and easy to use. Experience shows that the majority of people do not want to have to think about their chair when they are trying to work or activate a control to change its positioning and these controls are seldom used (24).

6.) Do no harm – A chair should not allow for discomfort, stress, pain or injury and should not constrain postures or force positions.

Posture in the field of dentistry has been greatly explored as they are more prone to musculoskeletal (MSK) diseases especially within the cervical (neck) and lumbar (lower back) spines (15). Dental nurses and dentists are a type of health care profession that require a high skill job in awkward sitting positions during clinical activity such as bending their head anteriorly and laterally repetitively over long periods whilst peering down the depths of their patient's mouths (28).

Various seats have been compared and analysed to find out which is the optimum chair to sit on for long periods whilst we work. There is evidence that the “ideal” ergonomic 90˚ sitting posture (knee angle and hip angle) actually increases the passive tension of hamstring muscles, causing a posterior pelvic rotation and resulting in a kyphotic sitting posture of the lumbar spine.

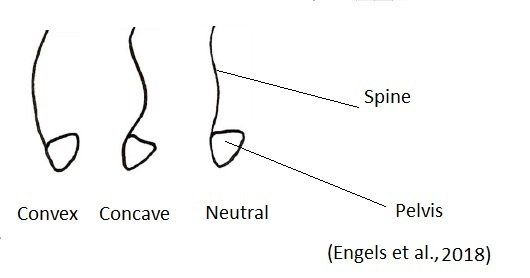

However, ergonomic recommendations, radiographic studies, and analyses from physical therapist and laypersons indicate that a sitting posture with a slight anterior tilt of the pelvis and lumbar lordosis may reduce the incidence of low back pain most efficiently.

The saddle stool (Figure 2) has been studied amongst the field of dentistry and has conflicting conclusions drawn for its effects on the spine. A study by Gadge and Innes (2007) found that the saddle seat was associated with significantly less lumbar discomfort but associated with more hip/buttock discomfort.

Da Silva et al. (2017) found that a saddle seat seems to promote a healthy posture, regarding maintenance of lumbar lordosis which is otherwise associated with lower disc pressure and suggested that it instead provided less physical workload to the arms and trunk during dental work. The literature does not yet provide a consensus on whether the saddle seat is a superior alternative to the conventional seat for maintaining optimal posture. In the context of the activities undertaken within this study, the standard stool has the least preferable combination of posture and muscle activity. It could be predicted that this type of seating will result in greater risk of lower back symptom reporting amongst dentists.

De Bruyne et al., (2016) compared the effect of using three different stool types on muscle activity and lumbar posture among dentists during certain dental screening tasks and discovered that individuals tended to sit with less lumbar flexion (-6°) than on a standard A-DEC DOCTOR’S STOOL (4°) or Ghopec (1°) stool.Findings also included the Ghopec stool tending to facilitate a less flexed lumbar position compared to the saddle stool which seemed to result in a hyperlordotic posture (9). Another interesting observation was that the presence of a backrest helped reduce the activation of the abdominal muscles and the study concluded that to recommend neutral posture, the Ghopec stool was considered the most suitable of the 3 stools that they investigated.

Another study by Grooten et al., (2013) found that the pelvis tends to be held in a posteriorly tilted position whilst seated on an office chair. They also concluded that the pelvis is in more of an anterior tilted position whilst standing and sitting compared to stable and unstable sitting on a Back App Stool or whilst seated on a saddle stool (16).

Annetts et al., (2012) investigated the effect of four different office chairs (saddle, vari-kneeler, swopper and standard) on the postural angles of the neck and lumbar-pelvic regions. They discovered that no chair seemed to consistently produce an ideal posture across all regions of the spine and they concluded that individuals' needs should be made priority when it comes to chair selection.

As a conclusion,

the biomechanics of sitting mainly focuses on measuring the position of the

spine, pelvis, muscle contractions, pressure distributions and boney contact on

the seat currently being used. In general, there is no

universal, ‘correct’ posture or no one “right way” to sit

as each individual is different with individual heights, body type and shapes (26). Modern ergonomic research should take different body types into

consideration and the nature of working behaviours that people adopt whilst

sitting (whilst at work) (29).

Tips For Staying Healthy at the Work Place (short video):

Sitting & Ill Health at The Workplace (Short Video):

A Simple Mid Back Exercise (video below):

- Mid back side bending exercise, hands clasped behind the head or neck, make sure to keep the chest up and avoid slouching by keeping the back straight.

- Have feet touching the floor.

- Slowly side bend the back to one side to the same side as demonstrated before performing the same to the other side.

References

1.) Akkarakittichoke, N., Janwantanakul, P. (2017) Seat Pressure Distribution Characteristics During 1 Hour Sitting In Office Workers With and Without Chronic Low Back Pain, Safety and Health at Work, OSHRI; 8: 212-219.

2.) Annettes. S., Coales, P., Colville, R., Mistry, D., Moles, K., Thomas, B., van Deursen, R. (2012) A Pilot Investigation into the Effects of Different Office Chairs on Spinal Angles, Eur Spine J, Springer, 21: 165-170.

3.) Beach, T.A., Parkinson, R.J., Stothart, J.P., Callaghan, J.P. (2005. Effects of prolonged sitting on the passive flexion stiffness of the in vivo lumbar spine. Spine J. 5, 145–154.

4.) Bolderman, F. W., Bos-Huizer2, J. J. A., Hoozemans, M. J. M. (2017) The Effect of Arm Activity, Posture, and Discomfort in the Neck and Shoulder in Microscopic Dentistry: Results of a Pilot Study, IISE Transactions on Occupational Ergonomics and Human Factors, 5: 92 – 105.

5.)Chaiklieng, S., Suggaravesiri, P. (2015) Ergonomics Risk and Neck Shoulder Back Pain Among Dental Professionals, Procedia Manufacturing, Elsevier; 3: 4900 – 4905.

6.) Callaghan, J.P., Dunk, N.M. (2002) Examination of the flexion relaxation phenomenon in erector spinae muscles during short duration slumped sitting. Clin. Biomech. 17, 353–360

https://www.clinbiomech.com/article/S0268-0033(02)00023-2/pdf

7.) Caneiro, J. O’Sullivan, P., Burnett, A., Barach, A., O’Neil, D., Tveit, O., Olafsdottir, K. (2010) The Influence of Different Sitting Postures on Head/Neck Posture and Muscle Activity, Manual Therapy, 15; 1: 54-60.

8.) Dankaerts, W., O’Sullivan, P., Burnett, A., Straker, L. (2006). Altered patterns of superficial trunk muscle activation during sitting in nonspecific chronic low back pain patients – importance of subclassification. Spine 31, 2017–2023.

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/4116/423bd11c5b01241a9c922ff83a532ed7b892.pdf

9.) De Bruyne MA, Van Renterghem B, Baird A, Palmans T, Danneels L, Dolphens M. Influence of differentstool types on muscle activity and lumbar posture among dentists during a simulated dental screening task. Appl Ergon 2016; 56:220–226.

10.) Dunk, N. M., Callaghan, J. P. (2005) Gender-Based Differences in Postural Responses to Seated Exposures, Clinical Biomechanics, Elseiver, 20: 1101–1110.

https://www.clinbiomech.com/article/S0268-0033(08)00317-3/pdf

11.) Dunk, N. M., Kedgley, A. E., Jenkyn, T. R., Callaghan, J. P. (2009) Evidence of a pelvis-driven flexion pattern: Are the joints of the lower lumbar spine fully flexed in seated postures? Clinical Biomechanics; 24: 164-168.

12.) Engels, P., Hokwerda, O., Wouters, J., de Rujter, R. (2018) The Saddle, in the Riding School and in the Dental Practice- An Analysis of Motion-Sequence and Function, OHDM, 17; 6: 1-10.

13.) Festervoll, I. (1994) “Office seating and movement” in Lueder, R. & Noro, K. (eds) 1994. Hard Facts About Soft Machines: The Ergonomics of Seating. London: Taylor & Francis. pg 418 –421.

14.) Gouvêa, R. G.,, Vieira, W. de A., Paranhos, L. R., Bernardino, I. de M., Bulgareli, J. V. Antonio., Pereira. C. (2018) Assessment of the Ergonomic Risk from Saddle and Conventional Seats in Dentistry: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis, Plos One, Assessment of the Ergonomic Risk in Dentistry, pp. 1-18.

15.) Gregory, D. E., Callaghan, J. P. (2008) Prolonged standing as a

precursor for the development of Low back discomfort: An Investigation of

Possible Mechanisms, Gait and Posture, Science Direct, 28: 86-62.

16.) Grooten (2013) Is Active Sitting As Sitting As We Think? Taylor and Francis, Ergonomics, 56; 8: 1304-1314.

17.) Gupta N, Christiansen CS, Hallman DM, et al. (2015) Is objectively measured sitting time associated with low back pain? A Crosssectional Investigation in the NOMAD study. PLoS One; 10:3.

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article/file?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0121159&type=printable

18.) Heneghan, N. R., Baker, G., Thomas, K., Falla, D., Rushton, A. What is the Effect of Prolonged Sitting and Physical Activity on Thoracic Spine Mobility? An Observational Study of Young adults in a UK university setting.

19.) Leivseth, G., Drerup, B. (1997) Spinal Shrinkage During Work in a Sitting Posture Compared to Work in a Standing Posture. Clin Biomech; 12: 409–18.

https://www.clinbiomech.com/article/S0268-0033(97)00046-6/pdf

20.) McGill, S. M., Brown, S. (1992) Creep response of the lumbar spine to prolonged full flexion. Clin Biomech; 7: 43–6.

https://www.clinbiomech.com/article/0268-0033(92)90007-Q/pdf

21.) McGill , S. M., Hughson, R. L., Parks K. (2000) Lumbar Erector Spinae Oxygenation During Prolonged Contractions: Implications for Prolonged Work. Ergonomics; 43: 486–93.

https://physoc.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1113/expphysiol.2006.033696

22.) Mork, P. J., Westgaard, R. H. (2009) Back Posture and Low Back Muscle Activities In Female Computer Workers: A Field Study, Clinical Biomechanics, Elseiver, 24: 169-175.

https://www.clinbiomech.com/article/S0268-0033(08)00317-3/pdf

23.) Nadine M. Dunk a,*, Angela E. Kedgley b , Thomas R. Jenkyn b , Jack P. Callaghan. (2009) Evidence of A Pelvis-Driven Flexion Pattern: Are the Joints of the Lower Lumbar Spine Fully Flexed in Seated Postures?

https://www.clinbiomech.com/article/S0268-0033(08)00348-3/pdf

24.) Nicola R Heneghan,1 Gemma Baker,2 Kimberley Thomas,3 Deborah Falla,1 Alison Rushton. (2018) What is the effect of prolonged sitting and physical activity on thoracic spine mobility? An observational study of young adults in a UK university setting, BMJOpen; 8.

https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/bmjopen/8/5/e019371.full.pdf

25.) Oliver, M. J., Twomey, L. T. (1995) Extension Creep In the Lumbar Spine, Clinical Biomechanics, Elseiver Science Limited, 10; 7: 363-368. https://www.clinbiomech.com/article/0268-0033(95)00001-2/pdf

26.) O’Sullivan, K., McCarthy, R., White, A., O’Sullivan, L. and Dankaerts, W. (2012) Lumbar Posture and Trunk Muscle Activation During A Typing Task When Sitting on A Novel Dynamic Ergonomic Chair, Ergonomics, Taylor and Francis; 1-10.7

27.) da Silva, V. A., Pedro, M. F., Campos, J. C. R. (2017) Biomechanical Study of Dentists Posture When Using A Conventional Chair Versus A Saddle Seat Chair, SPEMD, rev port estomatol med dent cir maxilofac, 58; 1: 39-45.

28.) Snijders, C. J., Bakker. M. P., Vleeming, A., R, Stoeckart, R., Stam. H. J. (1995) Oblique Abdominal Muscle Activity in Standing and in Sitting on Hard and Soft Seats, Butterworth Heinemann, Clinical Biomechanics; 10; 2: 73-78. https://www.clinbiomech.com/article/0268-0033(95)92042-K/pdf

29.) Springer, T. (2010) The Future of Ergonomic Office Seating, Knoll, Knoll Workplace Research, pp. 1-10.

30.) Vink, P., Porcar –Seder, R. Page de Pozo, A, Krause, F. (2007) “Office chairs are often not adjusted by end users” Proceedings of The Human factors And Ergonomics Society 51st Annual Meeting. Santa Monica, California: HFES. pg 1015 –1019.