Lower Back Pain & The Herniated Disc

- by Joanna Blair

- •

- 03 Feb, 2020

- •

Anatomy, Pathology & Management

The Herniated Disc

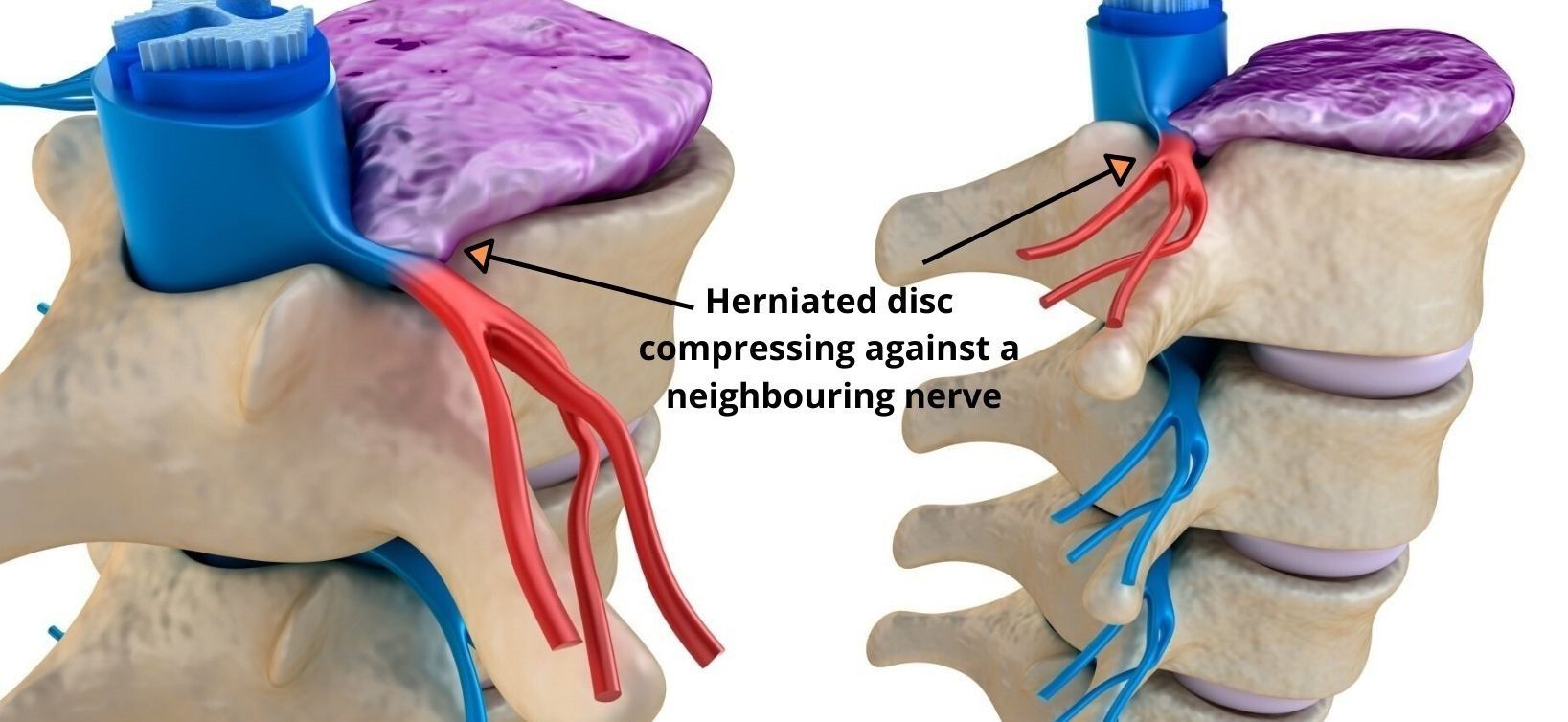

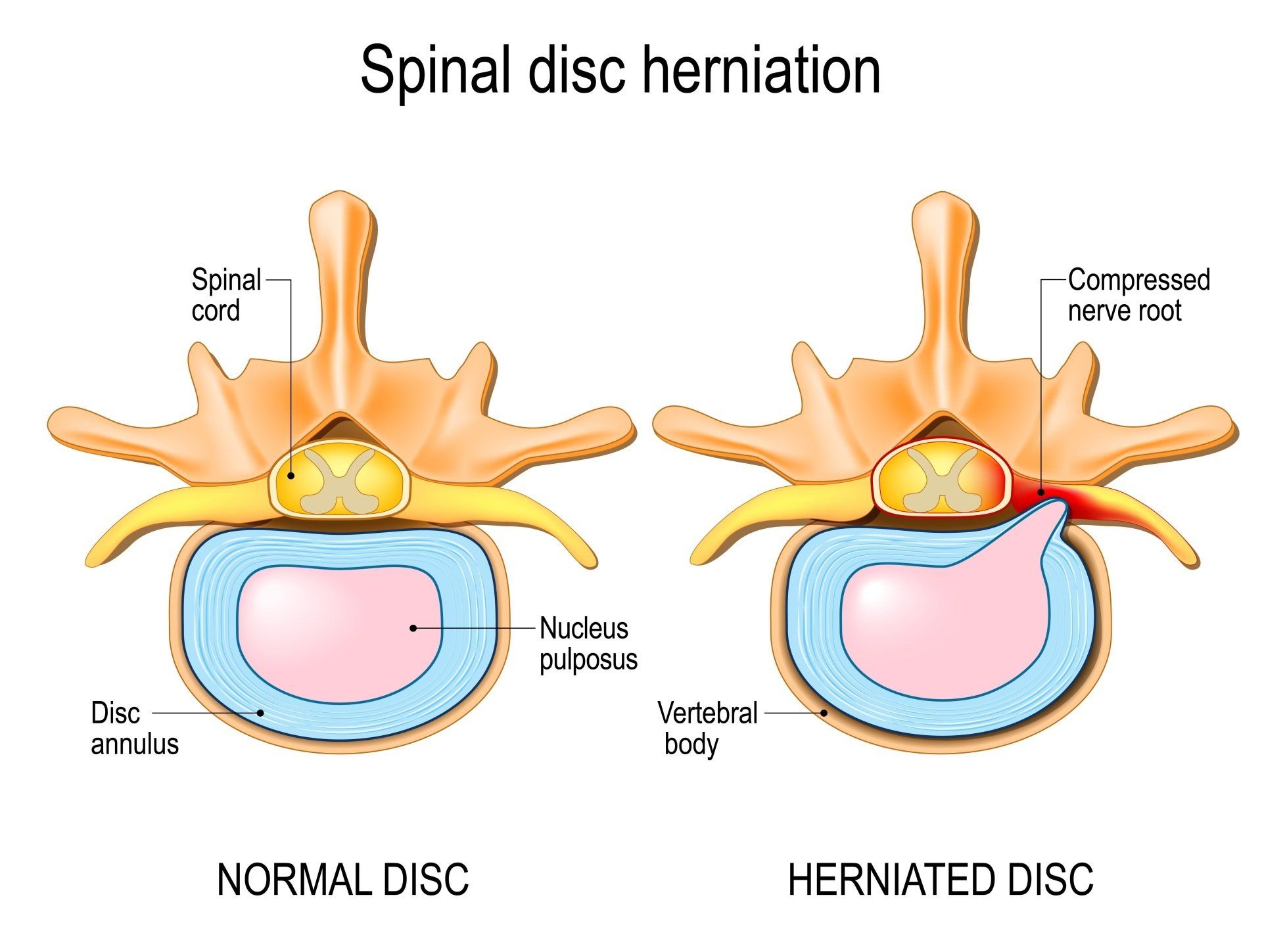

Intervertebral discs can, however, wear, split or herniate (bulge outwards).

The term herniation is a broadly used term to describe the displacement of focalised intervertebral disc material which is beyond the limits of the disc's space (13, 18). The classification of the herniated disc depends on either the annulus fibrosus (AF), the disc's outer and tougher covering. Or, the nucleus pulposus (the jelly like center of the disc) (22).

Disc herniations can be as a result of of a sudden injury to the structure such as a trauma, progressive degenerative changes or from repetitive stress from certain activities at work or during exercise (9, 22).

Biomechanical studies, (studies that analyse movement during activity) have mainly found that injury to a disc rarely occurs via axial compression alone (or spinal compression which causes shortening along the spine curvature) (8, 21). Instead, spine shrinkage and the development of disc herniations are more commonly caused from the repetitive motions of forward spinal bending (flexion) and rotation (torsion) (8, 26).

Anatomy of the Intervertebral Disc

- Annulus fibrosis

- Cartilaginous vertebral endplate

- Nucleus pulposus

The AF is the primary load-bearing component of the IVD and is composed of collagen fibers which are tightly arranged in 10-20 sheets of lamellae (2, 5). These are arranged and positioned in onion like rings around the central nucleus pulposus and the alternating alignment of fibers within the layers account for its strength and its ability to withstand the forces applied to the disc in all directions (2, 13). The directions of the layers of the annulus fibrosus alternate which adds to the strength of the annulus fibrosus. The posterolateral aspect of the annulus fibrosus has a greater content of vertically oriented fibers which weakens the disc tissue and explains why most tears or annular fissures occur at this particular region of a disc (19).

The AF of the lumbar spine IVDs are at their thinnest posteriorly by only having half the thickness of the anterior and lateral aspects of the annulus as there are fewer, finer and more tightly packed collagen fibers (lamellae) (2, 13). This makes the area of the AF more susceptible to injury at the lumbar intervertebral disc, especially if torsional (rotational) forces are applied.

Vertebral Endplates (EPs)

EPs are cartilaginous structures that are stongly attached to the intervertebral disc (IVD) via the annulus fibrosus but weakly attached to the vertebral bodies (2, 12). The endplates are situated superiorly and inferiorly in every disc and cover the whole length of the nucleus pulposus, but do not cover the entire extent of the anulus fibosus (2).

Nucleus Pulpsoes

Is an oval shaped hydrated gelatinous material contained within a ring of collagen fibres and contains mostly type II collagen which is elastic in nature and usually found in tissues that are exposed to pressure (2, 13).

The Herniated Disc; Pathology & Risk Factors

There are various personal and occupational risk factors for sciatica and prolapse discs which include (5):

- Smoking

- Obesity

- Age

- Height

- Mental Stress

- Exposure to vibration from vehicles

Types of Injury To the Intervertebral Disc

This is when a tear or fisure occurs within one or more layers of the annulus fibrosus and most are asymptomatic. Symptomatic annular tears or fissures without disc herniation are treated with NSAIDs and physical therapy (19).Thus, even if a disc prolapse or annular tear is discovered via medical imaging (e.g. MRI), pain is NOT necessarily experienced.

Pain from an annular tear might either be acute if the tear occurs suddenly or more chronic if there is a slower development of the annular fissure.If an annular fissure or tear is symptomatic, it may cause one of two findings:

1. Localised pains that are secondary to an annular tear which might be worse during certain movements and can stress or irritate the focal annular tear. In such cases, there is no radicular nerve involvement, and orthopaedic testing might be unrevealing.

2. Radicular symptoms secondary to irritation of the passing nerve root. In some cases, an annular tear can irritate a traversing nerve and cause radiculopathy (due to be explained in another blog post). If the annular fissure or tear is deep enough, disc material can herniate and irritate or compress neighbouring nerves or the spinal cord which can cause radicular symptoms including pain, paresthesia, and/or weakness depending on the extent of the nerve irritation (21).

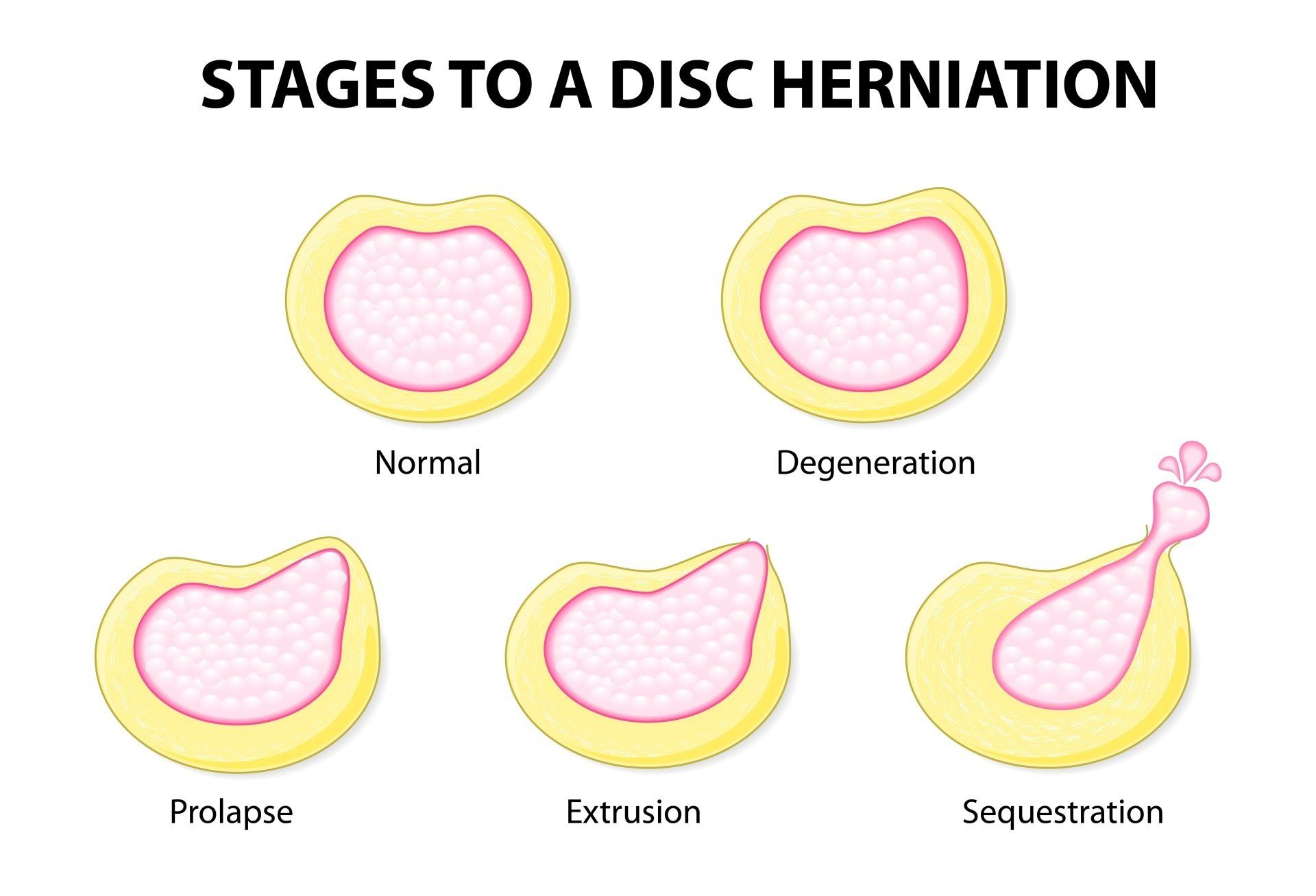

According to Ma (2015), the pathological classification of lumbar disc protrusion is controversial and the study describes four different types of lumbar disc protrusion. To keep matters simple, four problems of the intervertebral disc resulting from injury have been listed and briefly explained below:

Disc Protrusion

In a protruded disc, the disc bulges posteriorly without rupture or tearing of the annulus fibrosus (15). There is localised displacement of the disc material (more than 25% of the circumference of the disc) (Kushchayev et al., 2018).

Prolapsed Disc

The outermost fibers of the annulus fibrosus (AF) contain the nuceleus Pulposus (14).

Disc Extrusion

The annulus fibrosus (AF) is perforated and part of the nucleus pulposus (NP) moves into the epidural space (15).

Sequestration

When a formation of discal fragments from the annulus fibrosus (AF) and nucleus pulposus (NP) is no longer connected to the disc (15).

This form of disc herniation and figure does sound and look horrific compared to the other types listed above and one might think that surgical intervention would be the only recommendation for recovery. But, it has been known for patients to recover completely after nonsurgical conservative management.

The study by Orief (2012) revised six patient case studies who had experienced and been diagnosed with a symptomatic sequestrated disc levels L4-5 in three cases, L5-S1 in two cases, and C5-6 in one case.All six patients experienced associated acute radicular pain due to sequestrated intervertebral disc herniation and refused surgery as they were worried about complications. All six patients received conservative treatment that consisted of oral anti-inflammatory drugs, analgesics, muscle relaxants and physical therapy. Their radicular pains diminished and recovered within 3 to 6 weeks and resorption of the sequestrated intervertebral disc herniation was seen in their follow-up MRI scans after 4 to 9 months (18).

Carragee et al., (2003) categorized disc herniation into the following four groups and classified them as follows:

1) Type I, fragment-fissure herniation

2) Type II, fragment-defect herniation

3) Type III, fragment-contained herniation

4) Type IV, non-fragment-contained herniation.

Interestingly, this study found that the type II herniated disc category (the fragment-defect herniation group), with extruded fragment and defects on the posterior annulus, showed a 27% chance of recurrence and 21% chance of re-operation (3).

Type IV (non-fragment-contained group) showed 38% chance of remaining radiating pain and herniated disc recurrence (3).

Diagnosing A Herniated Disc

The diagnostic accuracy of taking a case history and performing a physical examination is still insufficient. Diagnostic imaging in patients is often used to assess nerve root compression caused by disc aviation or spinal stenosis and cauda equina syndrome. Imaging is also used to identify the affected disc level before surgery or medical intervention (7, 8).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT), x-ray and myelography are used as a form of diagnostic imaging.

XRay is the most commonly used form of imaging technique due to its lower cost and ready availability (7).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) Scans are mostly used out of all forms of imaging for suspected lumbar spine pathologies.

Computer Tomography (CT Scan) is less costly than the MRI, its testing time is shorter and the availability of CT scanners is larger in hospital settings but has the drawback of exposure to ionising radiation (7). Myelography involves the injection of contrast medium of the lumbar spine followed by x-ray CT or MRI imaging.

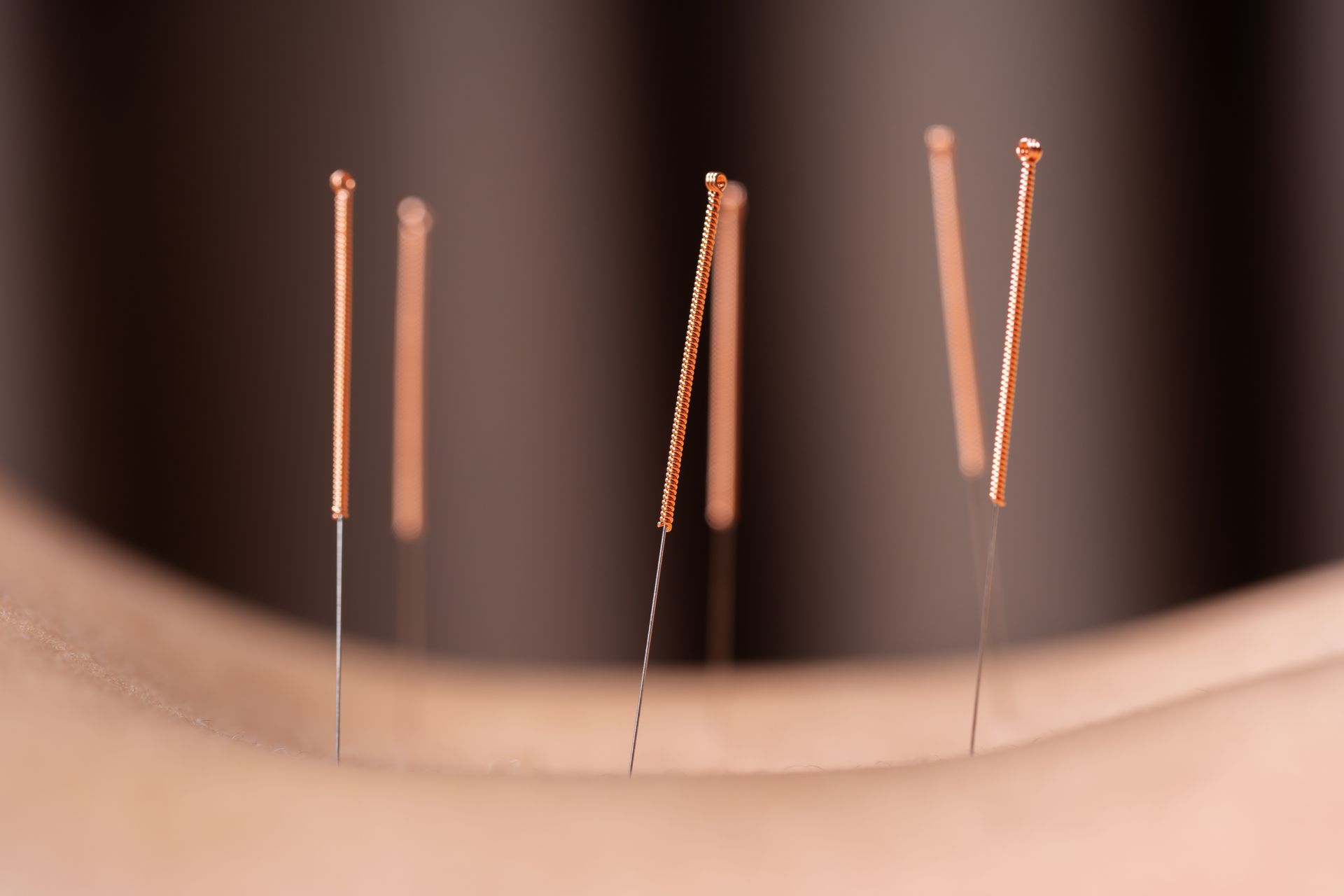

Treatment

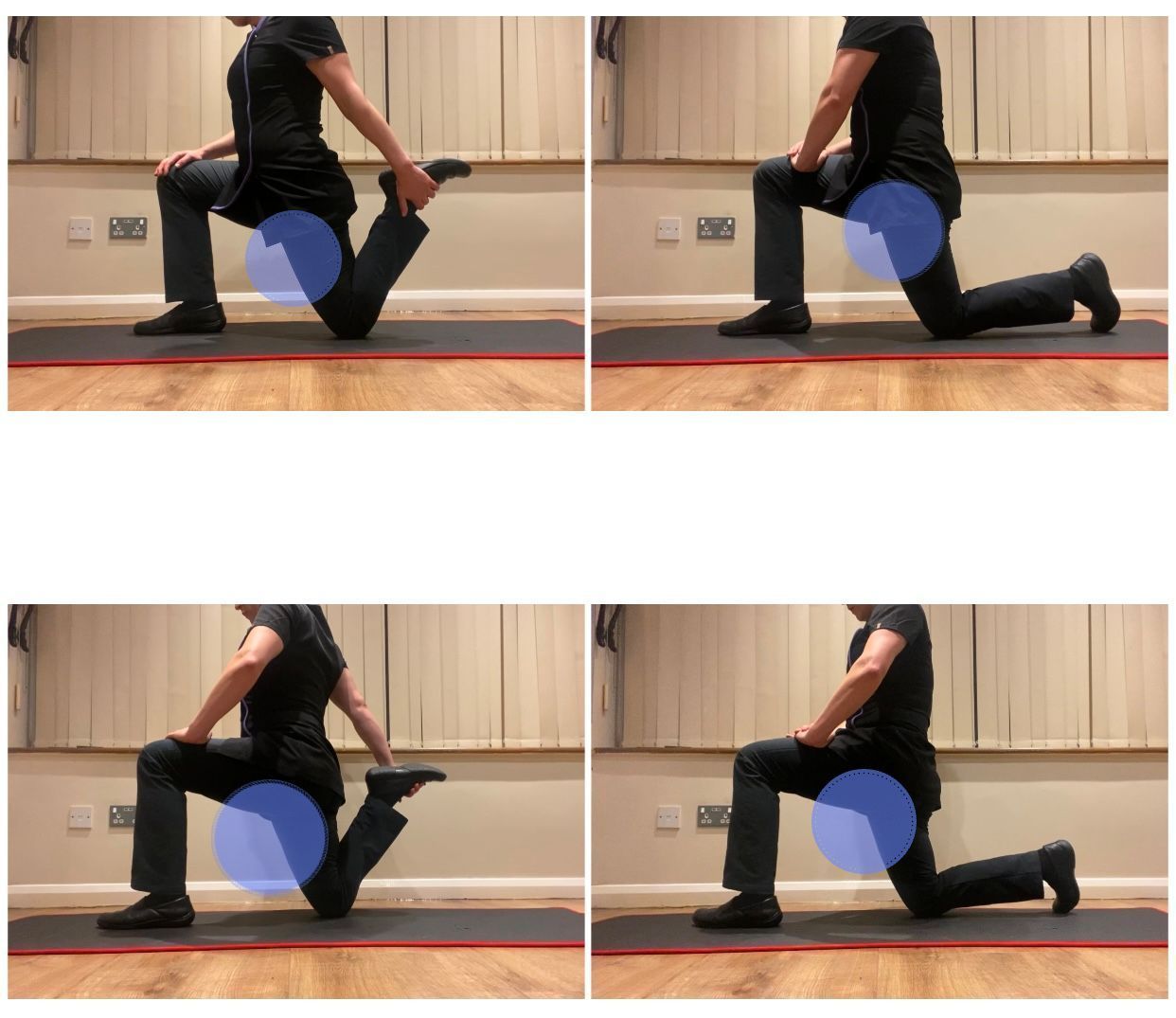

For manual therapy, caution regarding rotatory lumbar manipulation is advised, but manipulation has been demonstrated to improve symptoms of pain and body functional over sham treatment when rehabilitating patients with a lumbar herniated disc (17).

It has also been observed that skilled manual therapists who utilize mobilisation and manipulation above and below the affected spinal segment(s) and address the pelvis, or restrictions in the lower extremity, may decrease the amount of mechanical stress placed on the herniated disc(s).

Overall, manual therapy does play a role in pain management and potentially provide an optimal environment for the disc(s) to heal. This particularly being the case during the early and middle stages of rehabilitation.

As the patient progresses into the later stages of rehabilitation, however, the patient is encouraged to reduce their level of manual therapy and become more active via exercise programmes and increase their independence (18).

Shin (2014) reported that only 10% of all lumbar disc herniation cases are candidates for surgery which has an encouraging success outcome of 80-90% (19). The option for surgery is likely considered and recommended for if cauda equina syndrome is diagnosed (4). This is a rare condition which develops when a disc compresses the cauda equina and can cause unilateral or bilateral sciatica, motor weakness, and urinary incontinence or retention. Saddle anesthesia (loss of sensation in the area of the buttocks, posterior superior thighs, and perineum) is characteristic, and anal sphincter tone may be diminished (4). The surgery option also tends to be suggested if there is no pain relief at all after nonsurgical treatment amongst other factors such as the medical imaging reports and severity of pain (20).

References

1.) Amin, R. M., Andrade, N. S., Neuman, B. J. (2017) Lumbar Disc Herniation, Springer, CrossMark; 10: 507-516.

2.) Bogduk, N. (2005) Clinical Anatomy of the Lumbar Spine and Sacrum: 4th Ed., Elevier, Churchill Livingstone.

3.) Carragee, E.J., Han, M. Y., Suen, P. W., Kim, D. (2003) Clinical outcomes after lumbar discectomy for sciatica: the effects of fragment type and anular competence. J Bone Joint Surg Am; 85: 102–108.

4.) Deyo, R. A., Mirza, S. K. (2016) Herniated Lumbar Intervertebral Disk, The New England Journal of Medicine, Clinical Practice, 374; 18: 1763-1772.

5.) Fardon, D. F., Milette, P. C. (2001) Nomenclature and Classification of Lumbar Disc Pathology Recommendations of the Combined Task Forces of the North American Spine Society, Society of Spine Radiology, and American Society of Neuroradiology, SPINE, 26; 5: E93-E119.

6.) Frost, L. R., Brown, S. H. M. (2016) Muscle Activation Timing and Balance Response in Chronic Lower Back Pain Patients with Associated Radiculopathy, Clinical Biomechanics, Science Direct; 30: 124-130.

7.) Janardhana, A. P., Rao, S., Kamath, A. (2010) Correlation Between Clinical Features and Magnetic Resonance Imaging Findings in Lumbar Disc Prolapse, Indian Journal of Orthopedics, 44; 3: 263-269.

8.) Kadow, T., Sowa, G., Kang, J. D. (2015) Molecular Basis of Intervertebral Disc Degeneration and Herniations: What Are the Important Translational Questions? Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, CrossMark, Springer; 473: 1903-1912.

9.) Kim, J-H., van Rijn, R. M., van Tulder, M. W., Koes, B. W., de Boer, M. R., Ginai, A. Z., Ostelo, R. W. G. J., van der Windt, D. A. M. W., Verhagen, A. P. (2018) Diagnostic Accuracy of Diagnostic Imaging for Lumbar Disc Herniation in Adults With Low Back Pain or Sciatica is Unknown; A Systematic Review, BMC, Chiropractic & Manual Therapies, 26: 37.

10.) Koes, B.W., van Tulder, M. W., Peul, W. C. (2007) Diagnosis and Treatment of Sciatica, BMJ,

11.) Kushchayev, S. V., Tetiana. G., Jarraya, M., Schuleri, K. H., Preul, M. C., Brooks, M. L., Teytelboym, O. M. (2018) ABCs of the Degenerative Spine, 9; 2: 253–274

12.) Kuwahara, W., Deie, M., Fujita, N., Tanaka, N., Nakanishi,K., Sunagawa, T., Asaeda, M., Nakamura, H., Kono, Y., Ochi, M. (2016) Characteristics of Thoracic and Lumbar Movements During Gait in Lumbar Spinal Stenosis Patients Before and After Decompression Surgery, Clinical Biomechanics, 40; 45-61.

13.) Lundon, K., Bolton, K. (2001) Structure and Function of the Lumbar Intervertebral Disk in Health, Aging, and Pathologic Conditions, Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 31; 6: 291-306.

14.) Ma, X-L. (2015) A New Pathological Classification of Lumbar Disc Protrusion and Its Clinical Significance, Orthopedics Course, 7; 1: 1-12.

15.) Magee, D. J. (2002) Orthopedic Physical Assessment 4th Ed., Saunders, Elsevier Science.

16.) Merskey, H., Bogduk, N. (1994) Classification of Chronic Pain Descriptions of Chronic Pain Syndromes and Definitions of Pain Terms [2nd Ed.] Seattle, IASP Press.

17.) Moore, K. L., Agur, A. M. R. (2007) Essential clinical anatomy (3rd ed.). Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

18.) Orief, T., O, Y., Attia, W., Almusrea, K. (2012) Spontaneous Resorption of Sequestrated Intervertebral Disc Herniation, 77; 1: 146-152.

19.) Schoenfeld, A. J., Weiner, B. K. (2010) Treatment of Lumbar Disc Herniation: Evidence-Based Practice, International Journal of General Medicine, Dove Medical Press; 3: 209-214.

20.) Shin, B. J. (2014) Risk Factors for Recurrent Lumbar Disc Herniations, Asian Spine Journal,8; 2: 211-215.

21.) Tenny, S., Gillis, C. C. (2019) Annular Disc Tear, University of Nebraska Medical Center, StatPearls Publishing LLC.

22.) Vangelder, L. H., Hoogenboom, B. J., Vaughn, D. W. (2013) A Phased Rehabilitation Protocol For Athletes With Lumbar IVD Herniation, IJSPT, 8; 4: 482-516.

23.) Vialle, L. R., Vialle, E. N., Henao, J. E. S., Giraldo, G. (2010) Lumbar Disc Herniation, 45; 1: 17-22.

24.) Wankhade, U. G., Umashankar, M. K., Reddy, J. (2016) Functional Outcome of Lumbar Discectomy by Fenestration Technique in Lumbar Disc Prolapse – Retunr to Work and Relief of Pain, Journal of Clinical and Diagnosis Research, 10; 3: 09-13.

25.) Waturau, K., Deie, M., Fujita, N., Tanaka, N., Nakanishi, K., Sunagawa, T., Asaeda, M., Nakamura, H., Kono, Y., Ochi, M. (2016) Characterstics of Thoracic and Lumbar Movements During Gait In Lumbar Spinal Stenosis Patients Before and After Decompression Surgery, Clinical Biomechanics, Elseiver, 40:45-51.

26.) Wisleder, D., Smith, M. B., Mosher, T. J., Zatsiorsky, V. (2001) Lumbar spine mechanical response to axial compression load in vivo. Spine, 15, 26;18: E403-9.